A jaunty-looking Willy Wagtail ponders the surf, North Stradbroke Island. Photo courtesy of, and copyright, Michael Hines.

I don’t usually associate Willie Wagtails (Rhipidura leucophrys) with beaches, but some beautiful images taken at North Stradbroke Island by Michael Hines made me ponder just how ubiquitous these real characters are.

The Willy Wagtail is one of Australia’s most familiar birds, found throughout most of the continent. The name “wagtail” is confusing, because although it flicks and wags its tail from side to side, it is actually a member of the fantail family, and not one of the wagtails of Europe and Asia. [Bird: The DK Definitive Visual Guide]

Old shearers’ quarters, Currawinya National Park. Photo R. Ashdown.

A bird of many names

The Willie Wagtail was first described by ornithologist John Latham in 1801 as Turdus leucophrys.

John Gould and other early writers referred to the species as the Black-and-white Fantail. However, Willie Wagtail rapidly became widely accepted sometime after 1916. ‘Wagtail’ is derived from its active behaviour, while the origins of ‘Willie’ are obscure. The name had been in use colloquially for the Pied subspecies of the White Wagtail (Motacilla alba) on the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland. Other vernacular names include Shepherd’s Companion (because it accompanied livestock), Frogbird, Morning Bird, and Australian Nightingale.

Many Aboriginal names are onomatopoeic, based on the sound of its scolding call. Djididjidi is a name from the Kimberley, and Djigirridjdjigirridj is used by the Gunwinggu of western Arnhem Land. In Central Australia, southwest of Alice Springs, the Pitjantjatjara word is tjintir-tjintir(pa). Among the Kamilaroi, it is thirrithirri. In Bougainville Island, it is called Tsiropen in the Banoni language from the west coast, and in Awaipa of Kieta district it is Maneka. [Wikipedia]

A Willie Wagtail hunting dragonflies, Carnarvon Creek, Carnarvon National Park. Willie (sometimes spelled Willy) Wagtails often hawk for insects along creeks, launching into flight from boulders or other perches. We marvelled at this bird’s ability to snatch fast-moving and wary dragonflies out of the air. Photo R. Ashdown.

Found almost everywhere

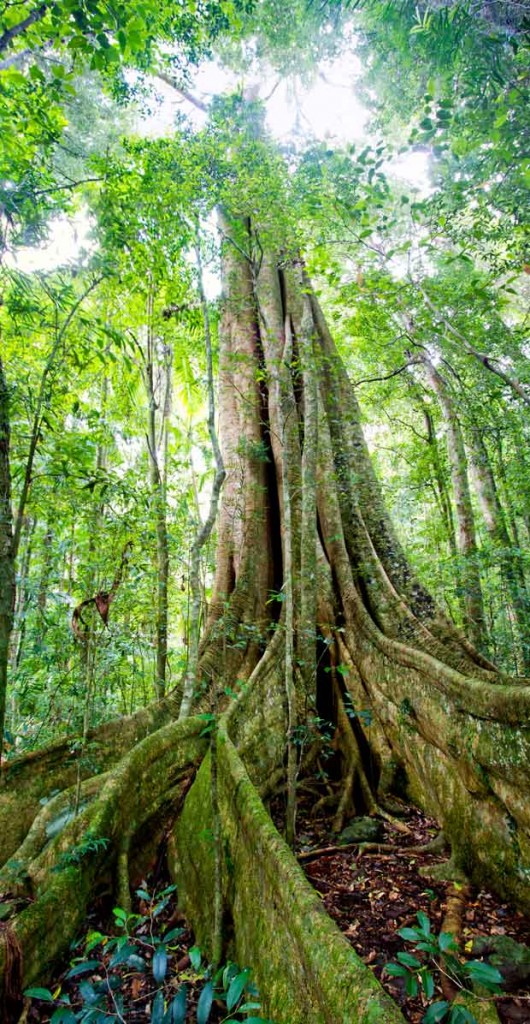

Exploring clearings, and familiar in urban areas, Willie Wagatils forage conspicuously in open places and are the only fantails to feed constantly from the ground. Through this capacity they have spread throughout Australia, avoiding only dense forests and treeless, perchless plains. [Reader’s Digest Complete Book of Australian Birds.]

Not your average backyard. Willie Wagtail on sand and pumice, Stradbroke Island. Willie Wagtails are one of five species of fantails (small flycatchers) in Australia. They are found throughout the mainland of Australia and, less commonly, in northern Tasmania. Mainly sedentary or locally nomadic, they tend to be solitary or to occur in pairs, but small flocks may form, where they are often mixed with species such as grey fantails. Photo courtesy of, and copyright, Michael Hines.

Small but fierce, with serious eyebrows

When breeding, Willy Wagtails defend their territory against even large predators, circling their attacker’s head in a figure-of-eight pattern uttering an aggressive ‘ricka-ticka-ticka-tick’. They defend their territory against other wagtails, enlarging their eyebrows in threat. Defeat is signalled by reducing the eyebrows and retreating. [Reader’s Digest Enclyopedia of Australian Wildlife.]

Willie Wagtail in flight above the old shearers’ shed, Currawinya National Park. When driving out west I’m always worried about hitting these birds as they dart out onto roads to grab insects, or to taunt drivers. I remember hearing from someone somewhere that Aboriginal people believe harming a Wagtail will bring you bad luck for years. I once stopped to collect an injured one on the side of the road driving to Carnarvon Gorge (maybe I’d get some ‘luck credit’), but it expired despite my best efforts to keep it breathing. I wondered how such a tiny, frail body could possess such a fierce spirit. On the way home I stopped and buried it near the spot I’d found it, under a tree I reckon it would like. I check out the tree every time I return that way. Photo R. Ashdown.

A big place in human life and story

Aboriginal tribes in parts of south-eastern Australia, such as the Ngarrindjeri of the Lower Murray River, and the Narrunga People of the Yorke Peninsula, regard the Willie Wagtail as the bearer of bad news. It was thought that the Willie Wagtail could steal a person’s secrets while lingering around camps eavesdropping, so women would be tight-lipped in the presence of the Willie Wagtail. The people of the Kimberley held a similar belief that it would inform the spirit of the recently departed if living relatives spoke badly of them. They also venerated the Willie Wagtail as the most intelligent of all animals.

Its cleverness is also seen in a Tinputz tale of Bougainville Island, where Singsing Tongereng (Willie Wagtail) wins a contest among all birds to see who can fly the highest by riding on the back of the eagle. However, the Gunwinggu in western Arnhem Land took a dimmer view and regarded it as a liar and a tattletale. He was held to have stolen fire and tried to extinguish it in the sea in a Dreaming story of the Yindjibarndi people of the central and western Pilbara, and was able to send a strong wind if frightened.

The Kalam people of New Guinea highlands called it Konmayd, and deemed it a good bird; if it came and chattered when a new garden is tilled, then there will be good crops. It is said to be taking care of pigs if it is darting and calling around them. It may also be the manifestation of the ghost of paternal relatives to the Kalam. Called the Kuritoro bird in New Guinea’s eastern highlands, its appearance was significant in the mourning ceremony by a widow for her dead husband. She would offer him banana flowers; the presence of the bird singing nearby would confirm that the dead man’s soul had taken the offering.A tale from the Kieta district of Bougainville Island relates that Maneka, the Willie Wagtail, darting along a river bank echoes a legendary daughter looking for her mother who drowned trying to cross a river flooding in a storm.

The bird has been depicted on postage stamps in Palau and the Solomon Islands, and has also appeared as a character in Australian children’s literature, such as Dot and the Kangaroo (1899), Blinky Bill Grows Up (1935), and Willie Wagtail and Other tales (1929). [Wikipedia]

Side of the highway, Marburg. Photo R. Ashdown.

A spirited and sweet voice

As a child I remember lying in bed at night listening to a strange bird call that would echo off the quiet houses — “sweet pretty creature” — loud and repeated for what seemed forever. Adults had no answers to my questions about this call, and it took me many years to work out that it was a Willie Wagtail. Birder Trevor Hampel has an informative post on his blog Trevor’s Birding about wagtails calling at night.

The nocturnal call of the Willie Wagtail is most commonly heard during moonlit nights and especially during the breeding season (August to February). From my own experience, the presence of a bright street light or car park lighting can also contribute to this phenomenon.

Once started, the song can continue for lengthy periods, often stimulating other birds nearby to also call. It is thought that the nocturnal song in Willie Wagtails is used to maintain its territory. During the night there is no need for parental duties such as feeding the young or protecting the nest, so the song can be used to consolidate the territory. Sound tends to carry further at night and there are fewer sounds in competition and this adds to its effectiveness. It has been found that most nocturnal songs are from a roosting bird some distance away from the nest.

Wagtail with captured dragonfly, Carnarvon Creek. Photo R. Ashdown.

Eats almost anything

The Willie Wagtail is an adaptable bird with an opportunistic diet. It flys from perches to catch insects on the wing, but will also chase prey on the ground. Wagtails eat, among other things, butterflies, moths, flies, beetles, dragonflies, bugs, spiders, centipedes, and millipedes.

They will often hop along the ground behind people and animals, such as cattle, sheep or horses, as they walk over grassed areas, to catch any creatures that they flush out. These birds wag their tails in a horizontal fashion while foraging. Why they do this is unknown but it may help to flush out hidden insects — or maybe they just like wagging their tails. For an in-depth study on the wagging tail of the wagtail, see here.

Wagtails take ticks from the skin of grazing animals such as cattle and pigs, and have even been seen doing this with lions in a zoo. Rod Hobson tells of seeing a photograph of one on the head of a crocodile in Papua-New Guinea. Photo R. Ashdown (thanks to Helen and Bill Scanlan).

Determined parents

Willie Wagtails usually pair for life. Anywhere up to four broods may be raised during the breeding season, which lasts from July to December, more often occurring after rain in drier regions.

Willie Wagtails build a cup-like nest, made of strips of bark or grass stems, and woven together with spider web or even hair from dogs or cats. They have even been seen trying to get hair from a pet goat. Photo courtesy Mike Peisley.

Wagtails may build nests on or near buildings, and sometimes near the nest of Magpie-larks, perhaps taking advantage of the aggressive and territorial nature of the latter bird, as it will attempt to drive off intruders.

From two to four small cream-white eggs with brownish markings are laid, and these are incubated for about 14 days. Both parents take part in feeding the young, and may continue to do so while embarking on another brood. Nestlings remain in the nest for around 14 days before fledging. Upon leaving, the fledglings will remain hidden in cover nearby for one or two days before venturing further afield. Parents will stop feeding their fledglings near the end of the second week, as the young birds increasingly forage for themselves, and soon afterwards drive them out of the territory. [Wikipedia]

Willie wagtail feeding young. About two-thirds of eggs hatch successfully, while only a third of these leave the nest as fledglings. Young wagtails are taken by other birds, cats and rats. Wagtails will defend the nest aggressively from intruders, and like Australian Magpies, will sometimes swoop at humans. Photo courtesy Mike Peisley.

A Wagtail confronts a Sacred Kingfisher that has dared to land in the vicinity of its nest. Photo courtesy Mike Peisley.

The last word

Widespread, well-loved. [Graham Pizzey. The Graham Pizzey and Frank Knight Field Guide to the Birds of Australia.]

Looking for dragonflies, Carnarvon Gorge. Photo R. Ashdown.

Wagtails on the web