The Australian night is rarely quiet. Many and varied are the weird and wonderful sounds of nocturnal animals, whether deep within the remote bush or floating above the urban jungle. Some of them are iconic, well-known calls; others are cryptic and mysterious — not really heard clearly or belonging to some strange, unknown beast in the shadows.

Twilight is a noisy time on a warm night in my home town of Toowoomba, as the roar of Bladder Cicadas (Cystosoma saundersii) drowns out traffic and conversation. Soon, there’s there’s the flap of leathery wings and the chattering, guttural shrieks of Black Flying Foxes (Pteropus alecto) as they argue over mulberries in the back yard. Walking the dog, the faint but far-carrying ‘ooom-ooom-ooom’ of a Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides) drifts over the street. Finding these avian ventriloquists is always trickier than expected. Then, as midnight approaches and the air cools a little, the highly evocative ‘mopoke’ call of a Southern Boobook Owl (Ninox novaeseelandiae) seems to resonate through the air and time itself.

While working at the Queensland Museum, I got to read the draft text for the first edition of that institution’s guide to everything, the Wildlife of Greater Brisbane. I was amused and intrigued by curator Steve van Dyck’s description of the call of the most vocal of all marsupials — the Yellow-bellied Glider (Petaurus australis). I laughed when I first tried to read it out loud —‘Ooo-cree-cha-cree-cha-chigga-woo-ja!’ Try saying that ten times fast, or well once, really. It was like something from Star Wars. I’d never heard this in the bush at the time and hoped I would one day soon.

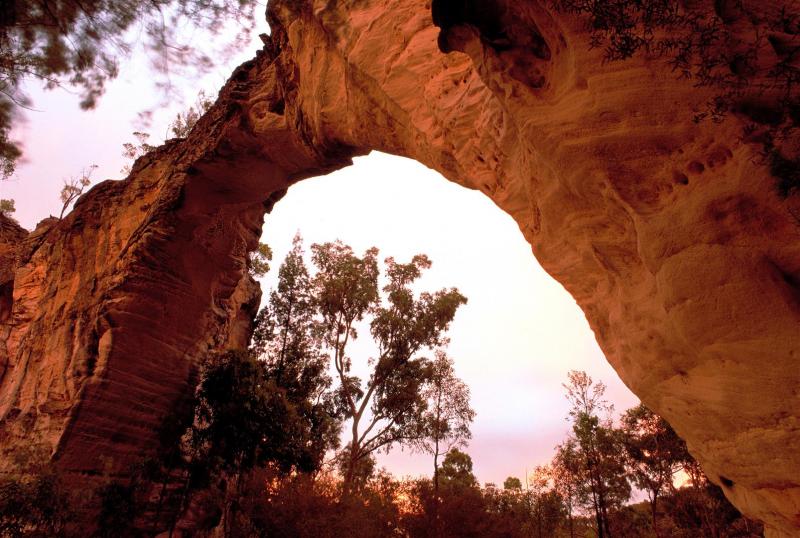

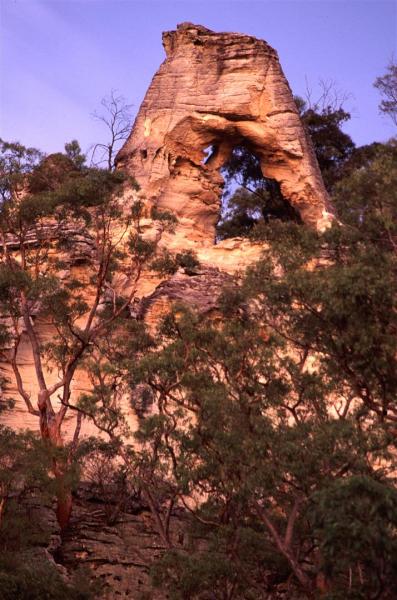

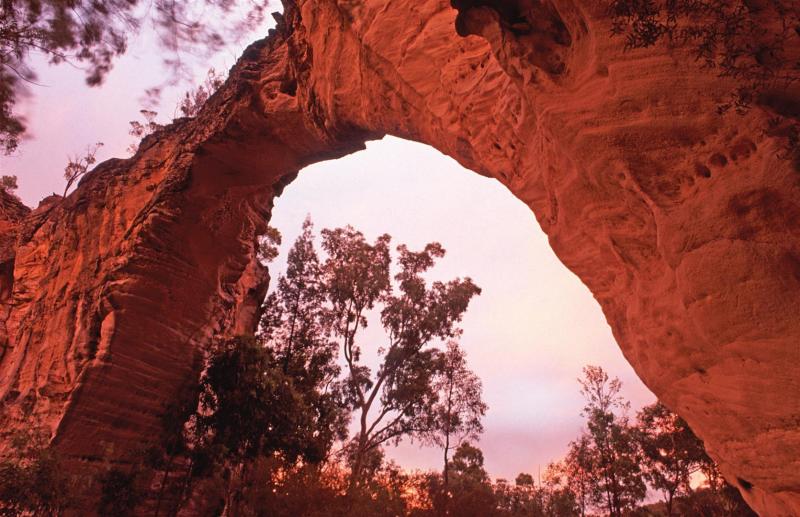

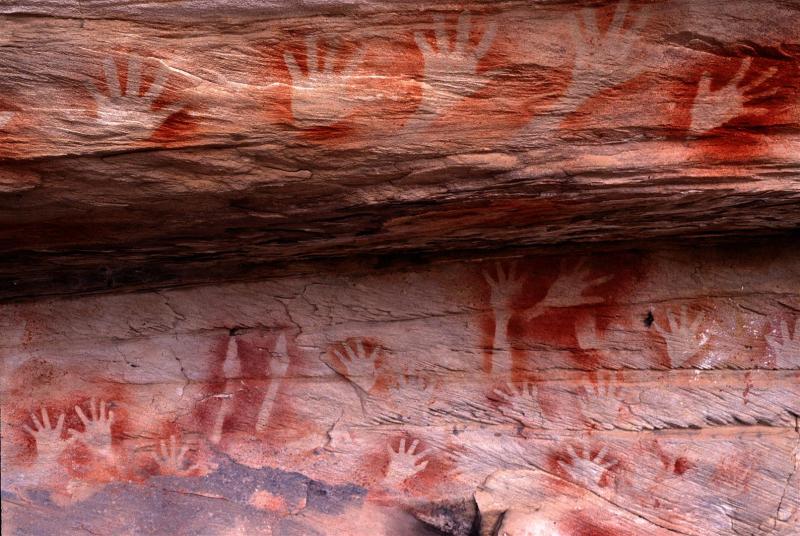

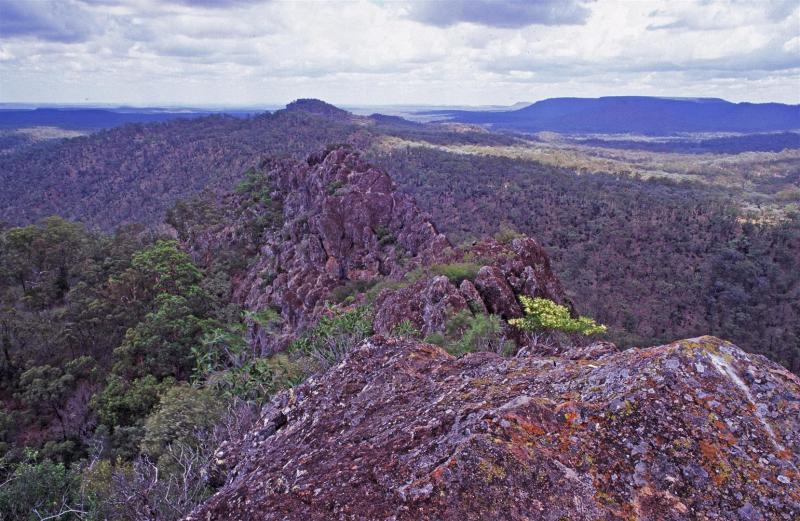

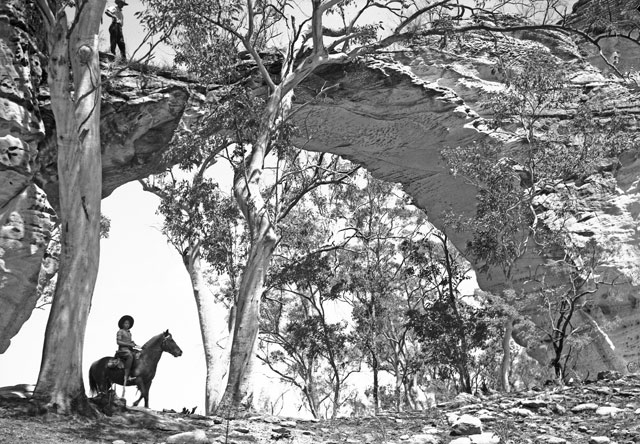

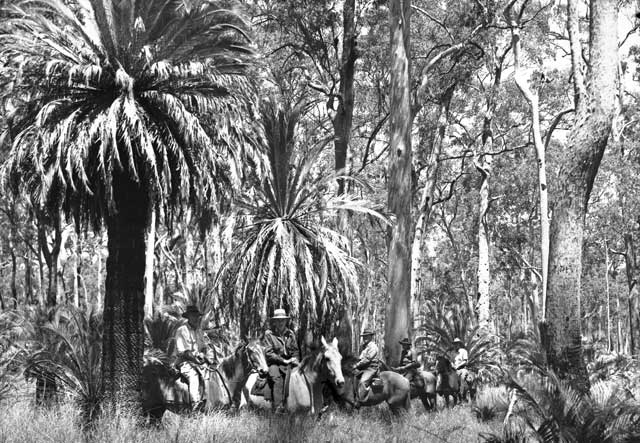

Carnarvon Gorge lies within the spectacular and rugged ranges of Queensland’s central highlands. Lined with vegetation and fed by the waters of numerous side gorges, Carnarvon Creek winds between towering sandstone cliffs. The gorge is a cool and moist oasis within the dry environment of central Queensland. Photo Robert Ashdown.

Wandering in Carnarvon Gorge National Park at night years later, I finally got to catch this vocal weirdness. As a family group of Yellow-bellied Gliders awaken and move from their day-time den, the racket begins. These nocturnal bush hooligans can be heard for about 500 metres.

Checking out the night and heading off to forage for breakfast, these beautiful and charismatic mammals will each call up to 15 times per hour. While their vocal repertoire includes moans, gurgles, panting, clicking, chirruping and purring, they tend to use two calls in particular (a moan and a gurgle) when gliding. They can glide up to 100 metres between trees, as they move quickly about their territory, which can be between 30 and 60 hectares. Researchers believe that their calls have a territorial function, as they vocalise more often near the boundaries of their territory than in its centre.

Five of Australia’s six glider species are found at Carnarvon Gorge, including the enormous Greater Glider (Petaurus volans) and the tiny Feathertail Glider (Acrobates pygmaeus). Greater Gliders are huge, reaching almost a metre between nose to tip of tail. They are solitary and quiet as they munch on eucalypt leaves. With a varied diet of insects, pollen, nectar and sap, the yellow-bellies on the other hand are active, social and rowdy — sugar and carbohydrate-fuelled hyperactives.

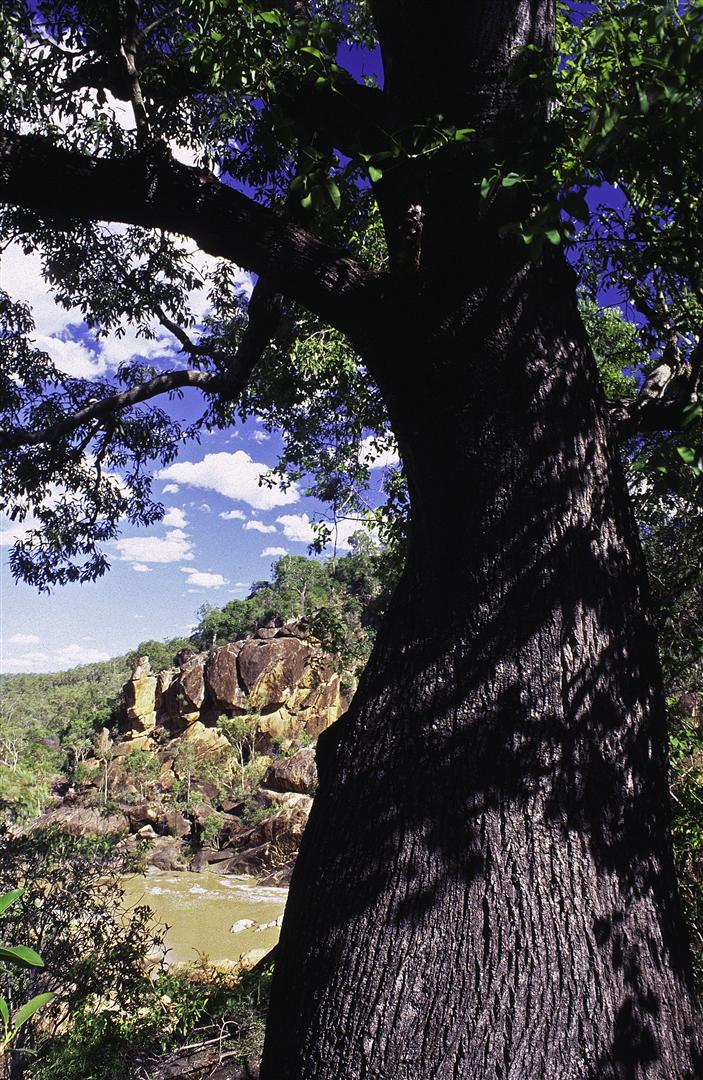

Carnarvon Gorge is home to a diverse range of unique and significant plants and animals—including five species of gliding marsupial. Photo Robert Ashdown.

As evening falls at Carnarvon Gorge, the night air is alive with the sounds of the night shift. Yellow-bellied Gliders, sleeping in dens with family members, begin to awaken. Active and rowdy, their strange calls resonate up to half a kilometre through the woodland surrounding Carnarvon Creek. Photo Robert Ashdown.

Photographing these animals is challenging, and I really have not tried that hard — I always enjoy just hearing them and sometimes spotting one. With the increase in the low-light quality of digital camera sensors, it’s easier to grab a decent shot of nocturnal mammals using a torch or flash these days, although using blinding flashes isn’t always a great idea with nocturnal mammals and they should probably be used sparingly. Ecologists and wildlife tour guides use a red filter over spotlights when tracking mammals, as this disturbs their vision far less.

Yellow-bellied Gliders are found down the east coast of mainland Australia from the Mount Windsor Tableland, west of Mossman in Far North Queensland, to the Victorian-South Australian border. In south-eastern Queensland, the glider is widely dispersed, but with a highly localised distribution and with possible disjunct (widely separated) populations in the Mackay and the Carnarvon areas.

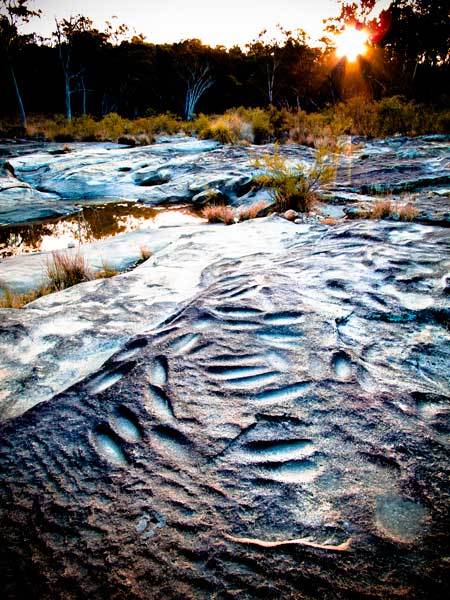

Yellow-bellied Gliders live in family groups comprising up to six individuals. With aerial glides of up to 100 metres, they cover great distances quickly; moving up to a kilometre from their regular den to feed. Photo Robert Ashdown.

Yellow-bellied Gliders feed on insects, nectar and pollen. However, as these foods are seasonal and scarce, they rely on the year-round source of clear, sweet-tasting sap of eucalypts, which they obtain by making V-shaped incisions with their lower incisors into the trunk bark of a number of different species of tree. Photos courtesy Bernice Sigley.

Australia’s largest gliding marsupial, the Greater Glider (Petaurus volans) is a silent and solitary mammal, feeding on gum leaves. These gliders can have a combined body and tail length of almost a metre, and weigh up to 1.5 kilograms. Photo courtesy Bernice Sigley.

Squirrel Gliders (Petaurus breviceps) are one of three smaller species of gliders found at Carnarvon. Sleeping in family groups in tree hollows, they emerge quietly at night to feed on gum sap, nectar and insects. Photo courtesy Bernice Sigley.

As with so many of the species we enjoy seeing, Yellow-bellied Gliders (and other glider species) face a range of threats.

Loss, and fragmentation, of habitat is the main challenge for these mammals, as it is with other wildlife. Gliders are also endangered by barbed-wire fences and introduced predators such as cats and foxes. As they are found in disjunct populations, they are also susceptible to local extinctions due to habitat degradation and climate-change.

- Click here for more information on the Yellow-bellied Glider.

With thanks to Bernice Sigley (naturalist, photographer and ex Ranger-in-Charge, Carnarvon Gorge), for the photos and the memories of some brilliant late-nights wandering the tracks at Carnarvon Gorge.