Cities and towns are tough places for wild animals to survive in. Yet some do very well, carrying on their lives all around us, often unnoticed and unappreciated.

Watching you go by. An Elegant, or Pretty, Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharus pulcher) warily warms up in the morning on a busy suburban fence.

I grew up in the suburbs of Brisbane in the 60s and 70s. It was a large sprawling town really, on the edge of becoming a city. There were chaotic urban blocks, old wooden houses with overgrown yards, huge mango trees, untidy footpaths, space, and lots of interesting wildlife.

At dusk a huge stream of flying foxes would darken the sky above our house at Manly in the Brisbane Bayside area, moving into the suburbs from the mangroves near the mouth of the Brisbane River, looking for food in backyards and the nectar of flowering eucalypts. Their colony is long gone, along with much of the mangrove forest they lived in — cleared for a huge port extension.

Grey-headed Flying Foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus). A much-loved feature of my urban childhood. Who could not be charmed by bats?

I would take a torch at night and stand under Queen Palms and peer up at these squabbling, fascinating mammals, Black and Grey-headed Flying Foxes. Their mysterious leathery wings and dog-like faces had me enthralled. I completed a poster on bats for a primary science competition, scouring libraries for anything I could find about these creatures, which was not a lot.

Old houses had dodgy tin roofs, where sparrows and possums could move in and cause havoc. And there were always reptiles. Carpet Snakes and large, fierce, fence-claiming Bearded Dragons.

Every backyard in Brisbane in the 60s and 70s had reptiles. And for a young fan of wildlife, Bearded Dragons were endlessly fascinating.

There were always skinks, those miniature marvels. Large, slow-moving Blue-tongued Skinks (Tiliqua fasciata) and the small brown, ground-dwelling Garden Skinks (Lampropholis delicata), which scurried about sunny patches on the edge of garden beds.

Then there were the darker, striped, wide-eyed and wary Fence Skinks (Cryptoblepharus pulcher), which raced along fences, defying all efforts to be caught.

I still look forward to seeing Fence Skinks (now usually referred to as Snake-eyed Skinks) while walking the dog in Toowoomba on sunny mornings. They warily watch the dog and I as we stroll past their early-morning fence gatherings, and I marvel at how they carry on their lives amidst our urban chaos. They seem to be a living link to my suburban childhood, clinging on as they do in the edge zones of our dwellings and structures and in the distant memories of sunny childhood yards long gone.

Old power poles, with cracked, flaking surfaces, provide fabulous habitat for the reptilian lovers of all things vertical.

One can only wonder what social dynamics are happening here. Many of this group have either missing tails or have regrown new ones — evidence of a perilous life near the bottom of the food chain. These dark bricks on an eastern-facing fence on a busy road warm quickly in the morning sun and are a much-loved hang-out for my local skinks.

As Steve Wilson says in Australian Lizards, a Natural History, “Lizards are extraordinarily successful at what they do best — being lizards.”

Skinks, the largest group of lizards in terms of number of species, have a wide range of adaptations and survival strategies that have seen them flourish in virtually all Australian habitats, including cities and towns. Snake-eyed Skinks must surely be at the top of the list for being able to survive around people.

There are currently 23 species of snake-eyed skinks (Cryptoblepharus) described in Australia. They are long-limbed, flat-bodied lizards — swiftly defying gravity as they race over rocks, fences, tree trunks and buildings. They are found across most of Australia, other than the south-eastern mainland and Tasmania. Their long-limbed, flattened characteristics are taken to the most extreme proportions in the Fuhn’s Snake-eyed Skinks (Cryptoblepharus fuhni), found only on the surfaces of granite boulders at Cape Melville in north-eastern Queensland.

My local fence-loving species, the Elegant (or Pretty) Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharus pulcher pulcher), is the ‘nominate’ subspecies, found across eastern Australia from Ingham in Queensland to Jervis Bay in New South Wales (including in inner suburban Sydney and Brisbane), while the subspecies Cryptoblepharus pulcher clarus is found in locations in southern Australia between South Australia and Western Australia. In my local bush areas I have seen Elegant Snake-eyed Skinks on trees and rocks, while in the suburbs they hang out on the human-engineered vertical surfaces of fences and walls.

Perhaps the most successful skinks across the urban spectrum are the snake-eyed skinks (Cryptoblepharus spp.), also appropriately called fence or wall lizards. They do not reach as far south as Melbourne, but they thrive in most other cities between Perth and Cairns. In a natural environment they live on vertical rock and tree surfaces, and the shift to human structures has been an easy one. Snake-eyed skinks even occupy the walls of buildings well within the central business districts. — Steve K Wilson Australian Lizards, A Natural History

An Elegant Snake-eyed Skink in the wild, seen here on sandstone in bushland at White Rocks reserve near Ipswich.

Clinging effortlessly to the sheer trunk of a dead ironbark tree (where there are plenty of gaps to hide in). Highwoods, near Jimbour, Darling Downs.

Other species of snake-eyed skinks include the Coastal Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharus litoralis), which stays close to the rocky coasts of north-eastern Queensland and the Northern Territory, where it avoids waves to feed on wave-drenched rocks. The Agile Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharis zoticus) is a rock specialist, living on the sandstone escarpments of north-western Queensland and the Northern Territory.

The Coastal Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharus litoralis). Prince of Wales Island, Queensland. Image courtesy Steve K Wilson.

Metallic Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharus metallicus). Old Laura Homestead site, Rinyirru National Park.

Snake-eyed Skinks have adapted well to life in the suburbs and in harsh bush environments. While they are found in deserts right through into areas with high rainfall, they usually always dwell on exposed vertical surfaces, places usually free of moisture. Small skinks such as the Snake-eyes therefore face a real risk of dehydration due to water loss. The smaller a skink, the greater the ratio of surface area to volume, and therefore the more vulnerable it is to dehydration.

The surface of a skink’s eye can potentially lose a great amount of water through evaporation. A strategy that some skinks have evolved (separately in different parts of the world) to avoid this is the presence of a clear, waterproof cap that covers the eye — a transparent, fixed eye cover known as a brille. This is the skink’s lower eyelid, which is permanently closed in an upright state, a condition known as ‘ablepharine’. The most widespread ablepharine skins are the snake-eyed (named after their lidless, ‘staring’ eyes).

The transparent, fixed eye cover (known as a ‘brille’), that earns this skink the common name ‘snake-eyed’.

Covering the eye with an immovable transparent window has evolved independently among small skinks worldwide. More than eight Australian species exhibit the condition. At one time, all skinks that adopted this water-saving strategy were lumped together in one genus, Ablepharus. The name appears in old Australian reference books and was applied to unrelated species ranging from central Victoria to central Europe. — Steve Wilson and Gerry Swan. What Lizard is That?

As they are able to withstand desiccating conditions, snake-eyed skinks have been able to travel across oceans. The genus extends from southern Africa and out across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, where they are found living on isolated small islands. Their moisture-resistant eye-caps have assisted them in surviving such long-distance travels.

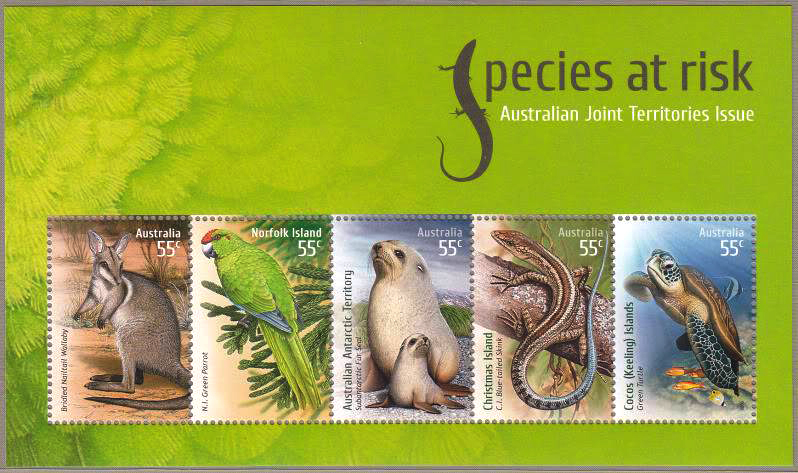

The Christmas Island Blue-tailed Skink (Cryptoblepharus egeriae) is a species of snake-eyed skink that originally travelled to Christmas Island from Australia, or islands ecologically connected to it. Once common and widespread in the 1980s, this species was driven to extinction by 2010 by an introduced predator, the Yellow Crazy Ant (Anoplolepis gracilipes). However, rangers on the island saved 66 skinks and a captive breeding program in Australia began.

Jon-Paul Emery researched the Christmas Island Blue-tailed Skink on Christmas Island as part of his PhD thesis. He says, “Captive breeding of the aptly-named blue-tailed skink was incredibly successful; so much so that Parks Australia in 2017 began trials re-introducing the skink back onto the island to try and establish populations in predator exclusion sites. My research investigated the ecology of the species as well as ways to monitor the skinks and how they responded post-release. I also looked at the threats that affected how well the skinks did within the translocation sites.”

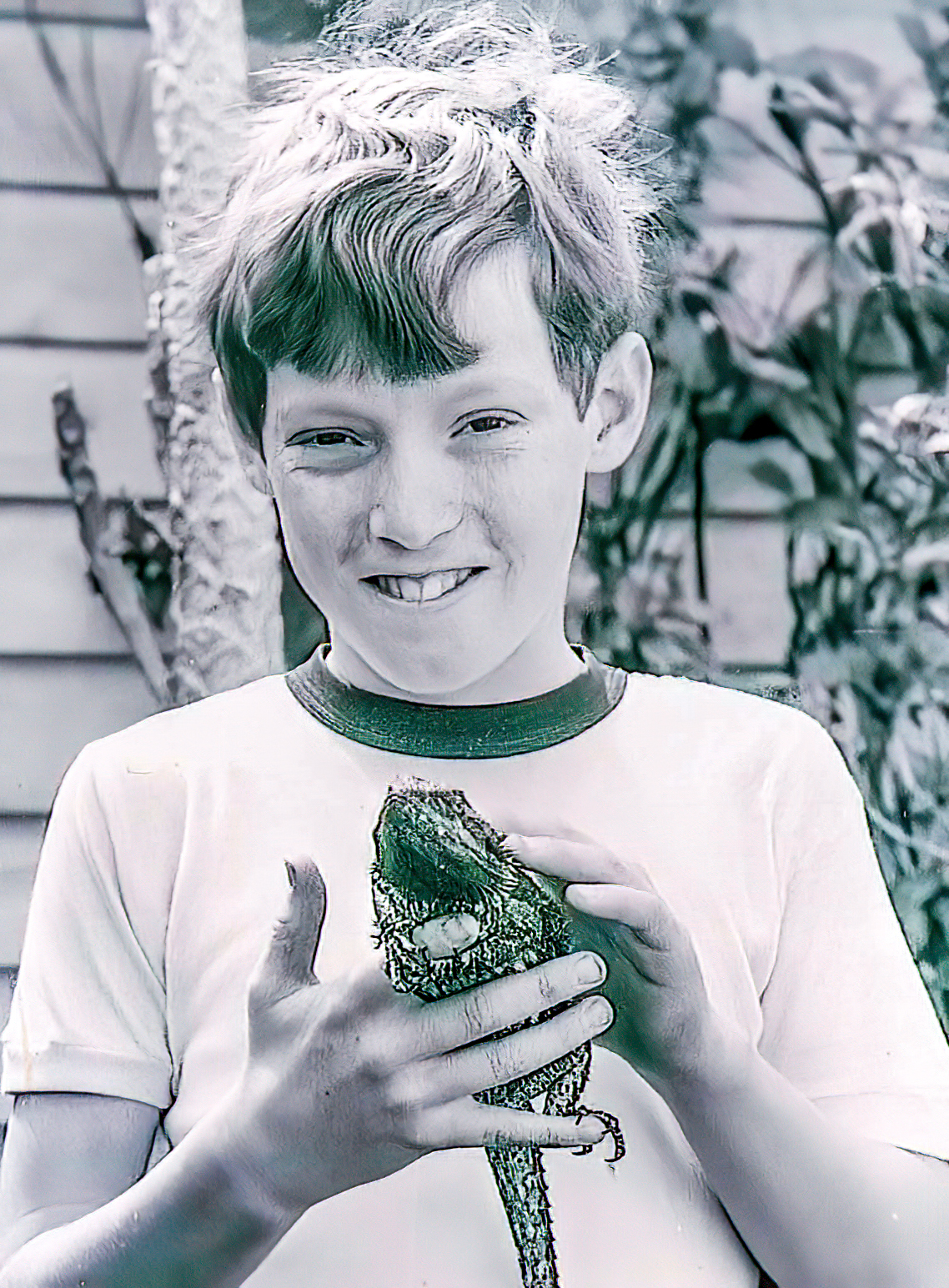

Researcher Jon-Paul Emery with a Shingleback (Tiliqua rugosa), one of Australia’s largest skinks. Photograph courtesy Jon-Paul Emery.

Jon-Paul’s research has helped inform ongoing management of the species, with translocations been undertaken to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (an archipelago 1,000km away) and additional sites on Christmas Island.

In the safer suburbs of Queensland, Snake-eyed Skinks race out to catch passing insects such as flies, cockroaches, bugs, wasps and grubs. They tend to capture more flying insects than other ground-dwelling lizards. They have been observed carrying out ‘kleptophagy’ — a form of piracy whereby they rob ants of the food they are carrying. They have also been seen looting mudwasp nests to take the arthropod prey intended for the wasps’ larvae. When eating ants, they take the tasty ant alates while avoiding worker ants. In my area, naturalist Rod Hobson has watched them eating Black House Ants (Ochetellus glaber). In the Great Victoria Desert, Buchanan’s Snake-eyed Skinks (Cryptoblepharus buchananii) mainly eat termites, small spiders, bugs and beetles.

Skinks, however, are near the bottom of the food chain, and like all creatures down the list, they have many predators out to get them — including birds, snakes, cats, curious children and even spiders. They stay close to cover, are very wary, and dart off rapidly to nearby crevices at the slightest sign of approaching trouble. They can shimmy across vertical surfaces and their flattened bodies allow them to hide in narrow places.

A passing ant is seized. Snake-eyed skinks have been recorded staking out ant trails to rob the insects of the prey they are carrying.

Tables turned. A Red-back Spider makes a meal of an Elegant Snake-eyed Skink on a footpath in the main street of Toowoomba. Note how the skink has cast off its tail in an attempt to escape the spider’s clutches.

Despite being a common species, a recent study published in the Australian Journal of Zoology is one of the first to provide a detailed look at the life-history of the Elegant Snake-eyed Skink.

Living for about three years, these skinks breed in spring and summer in southern Queensland and all year round in hotter northern places. Females lay two eggs, and there have been documented cases of communal nesting where up to four females lay eggs at the same time in one place.

Snake-eyed skinks lay small eggs, probably similar in appearance to these of the Delicate Sun Skink. Although they are common in urban environments, very few egg clutches of snake-eyed skinks have ever been recorded. It is reported that some species lay eggs in communal sites, including the Striped Snake-eyed Skink (Cryptoblepharus virgatus), which uses ant plants (Rubiacceae) on Horn Island in the Torres Strait as communal nest sites. Up to 20 eggs and four hatchlings were recorded together at one site.

[Click on images in the gallery above for a closer view.]

I hope that that suburban fences may forever be adorned with the skittering shapes of miniature snake-eyed reptiles. The urban wilderness would be far more boring without them.

Living on ruined buildings where the humans have long gone, Peel Island (Teerk Roo Ra National Park).