The Black, or Fork-tailed, Kite (Milvus migrans) is a hawk found mainly in Australia throughout the northern and inland parts of the country.

It’s a sociable raptor often seen around human settlements, where large flocks frequent rubbish dumps, stockyards, abbatoirs and roads.

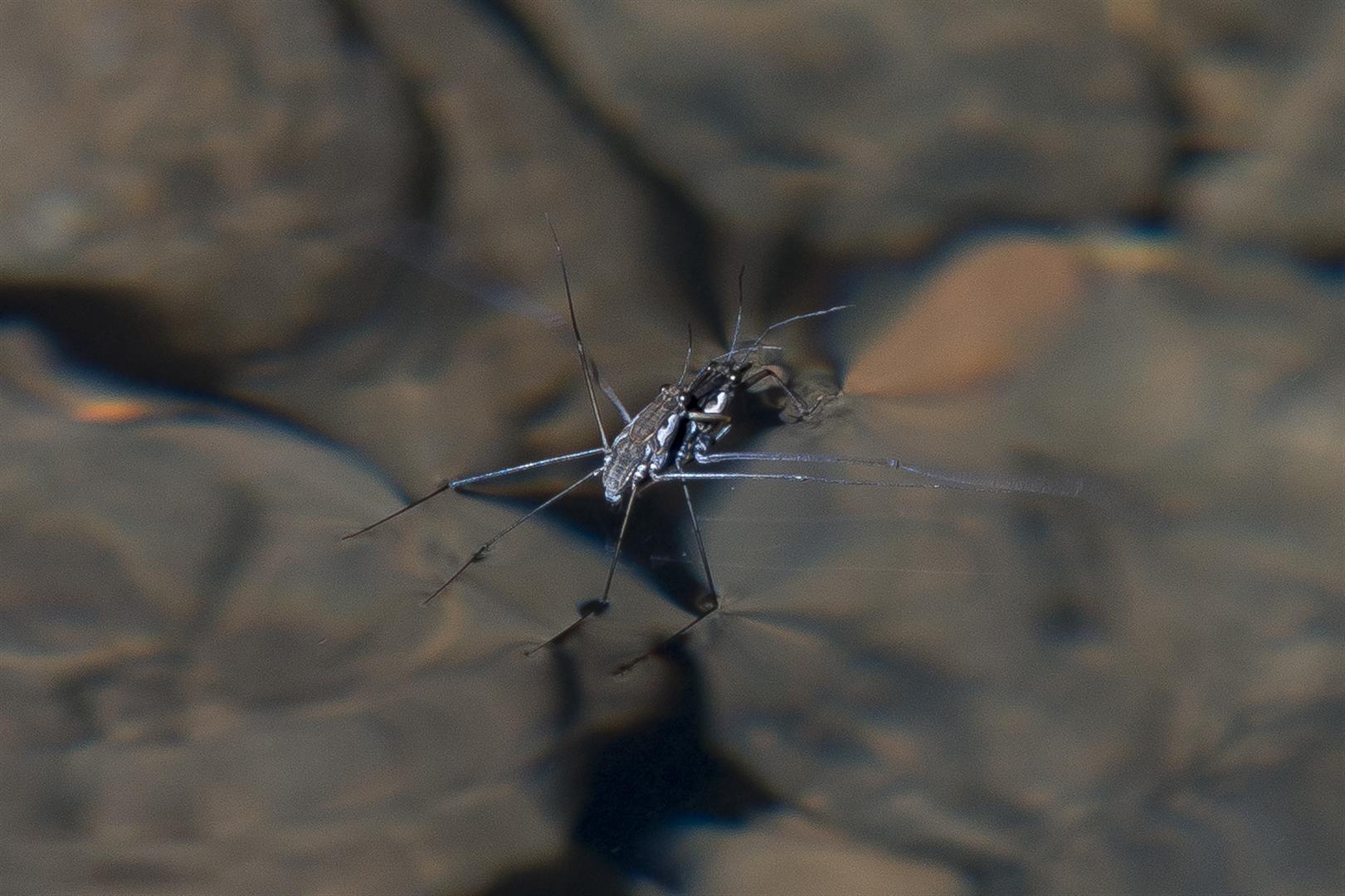

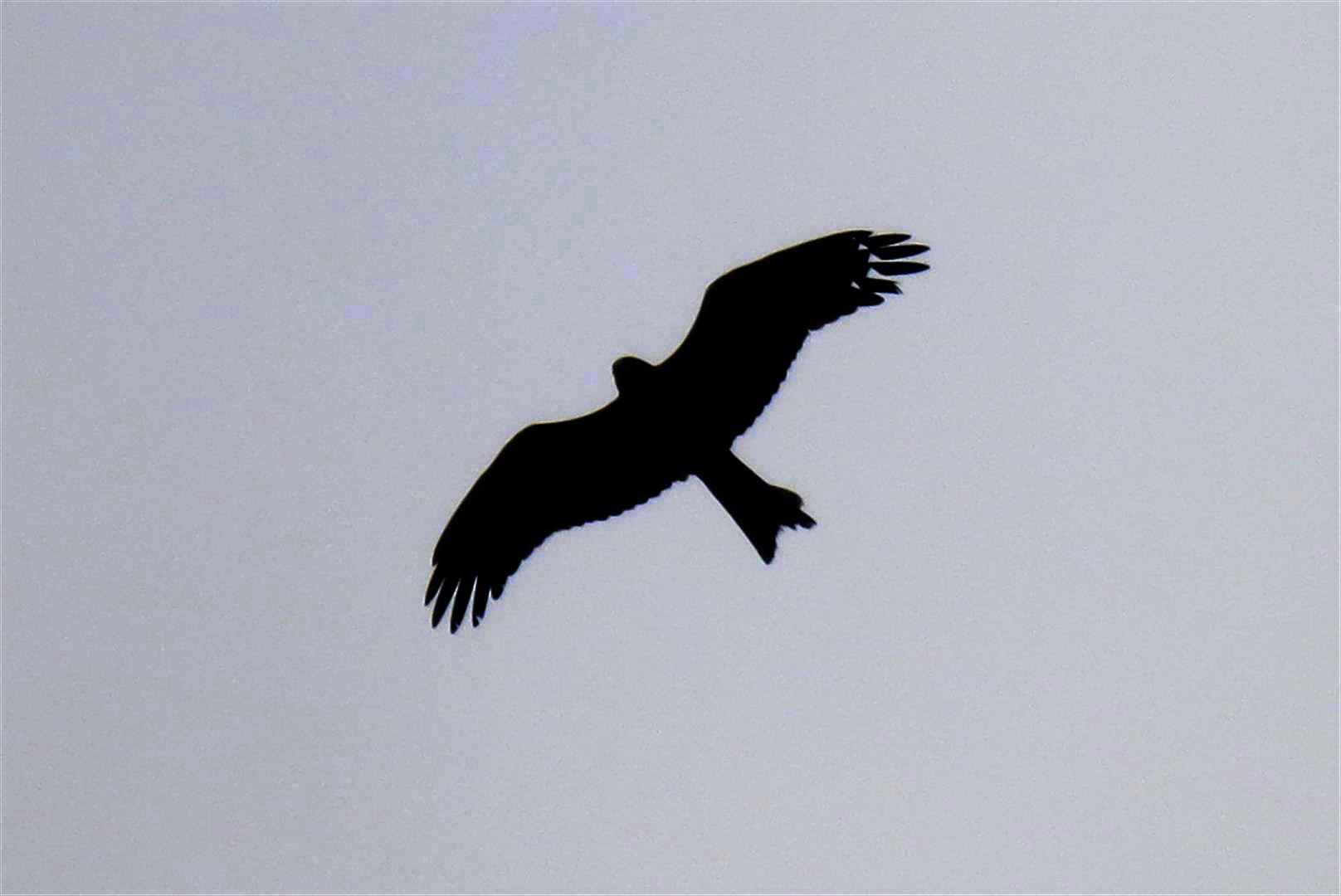

The Black (or Fork-tailed) Kite is a “medium-sized, scruffy brown soaring hawk that often gathers at carrion, refuse and fires+.” This kite is about 47-55 cm long, with a wingspan of 120-139 cm. “Floats overhead on long, drooped wings with prominent spread ‘fingertips’; twists, tilts its long, forked tail.^” Photograph copyright Tom Tarrant, used with permission.

This species is also found across much of the world , including Europe, Africa, Asia and New Guinea. In Europe the populations are highly migratory, hence the specific name migrans. Populations of the bird in Australia do not regularly migrate, but are known to occasionally ‘irrupt’ in areas beyond their usual range.

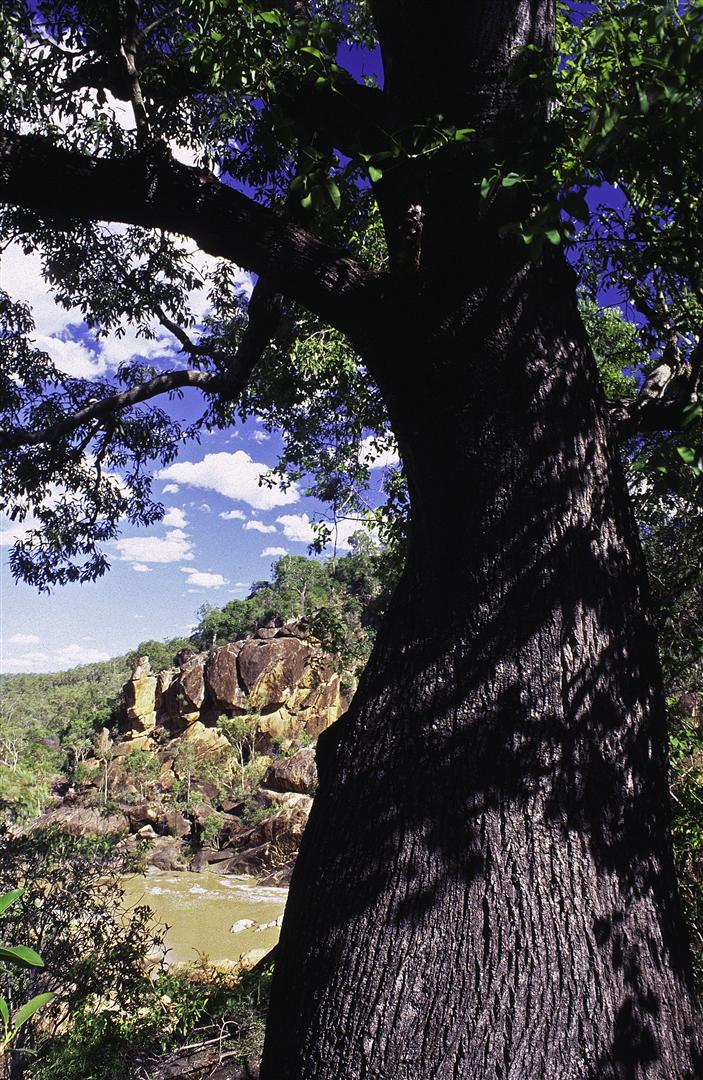

Black Kites soar or glide on flat or slightly arched wings, often with head hunched forward while body and wings twist and change position. They are highly manoeuvrable birds, side-slipping to snatch food from the ground or water. Photograph copyright Tom Tarrant, used with permission.

While seen occasionally about Toowoomba in small numbers or individuals, a large movement of these birds across town is from all accounts a fairly uncommon event. However, this is indeed what’s happened over the last month, with groups of these birds numbering up to perhaps a hundred, or even more, moving across the town. Other species of raptor have been seen at times moving with, or through, the groups.

A flock of at least 50 Black Kites moving above Toowoomba, 14 April 2013. Photograph by Justin Shiels.

While walking the dog in the park we spotted a large flock of these kites overhead, circling loosely on thermals and heading slowly east. As our small dog sat by itself in the open field, one bird suddenly appeared above us, peering intently at our little mutt.

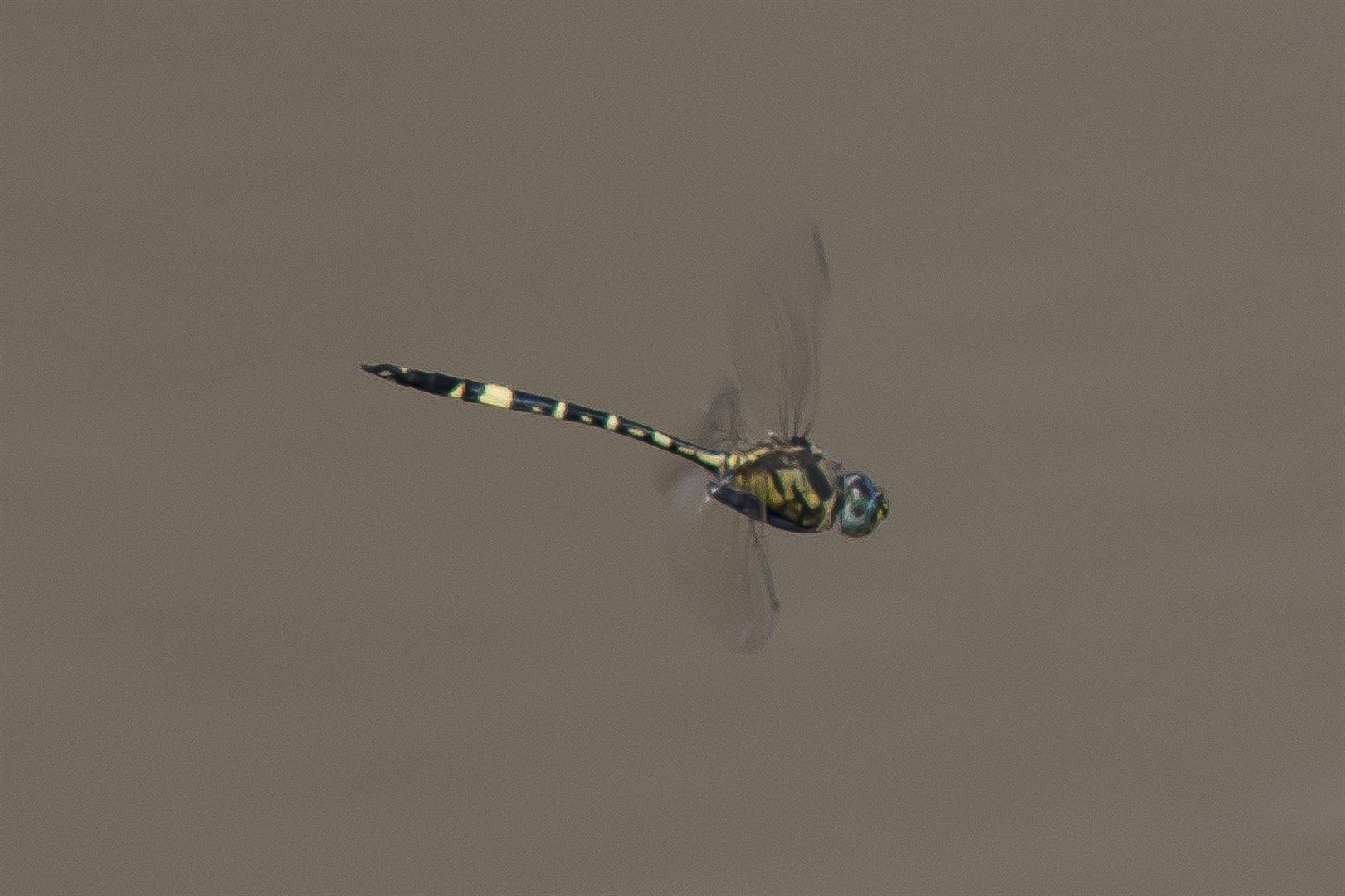

A solitary Black Kite materialises low over us, twisting its head to peer at our small, worried dog.

Pluto, the small, black, worried dog, is offered up as a sacrifice to the flock of raptors, all in the good cause of attempting to get a better bird photo. She does not look impressed. Black Kites eat all sorts of animals and carrion, including mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians, invertebrates and road-kill and other carrion. They patrol fire-fronts and roads and follow other birds and farm machinery to snatch flushed prey. Black Kites also love human scraps and forage by soaring and quartering before dropping on prey, according to Stephen Debus. I’d say this bird was wondering if our small, black hound was recent road-kill. Photograph by Robert Ashdown.

Says raptor expert Stephen Debus, “The Black Kite’s most characteristic behaviour is its effortless circling in inland or tropical skies, in flocks sometimes numbering hundreds or even thousands. It can ascend beyond the range of human vision or suddenly appear overhead having descended from invisible heights.” Which is what this one pretty much did.

The dog was clearly threatened, peering up and growling before running to hide between human feet. It was hilarious to see this notorious bird-chaser on the receiving end for once!

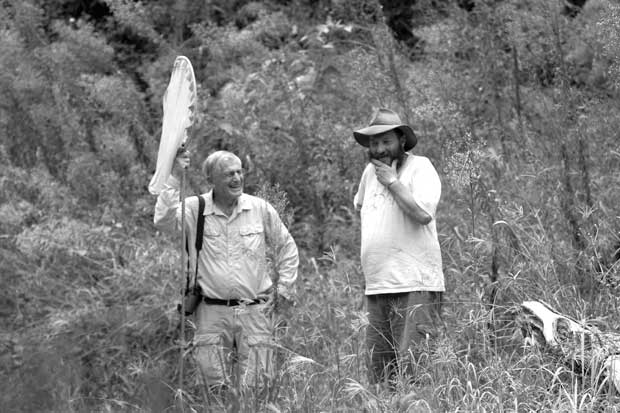

The Black Kite is also known in Australia as the Kimberley Seagull because of its habit of gathering in large numbers to scavenge an abundant food source. They have also been known to flip over Cane Toads to feed on them while avoiding the amphibian’s poisonous parts. Photo copyright Tom Tarrant, used with permission.

See comments for updates.

Thanks to Justin Shiels, Tom Tarrant, Mick Atzeni, Richard Jeremy.

*Thanks also to Ian Menkins for the great collective noun. While the Oxford Dictionary associates the use of the collective noun ‘kettle’ for a group of fish, the term has also been used for hawks when flying in large numbers (see 1, 2) I might be stretching things a bit by using it with kites (too bad, it sounds good).

References:

+ Debus, S (1998). The Birds of Australia. A Field Guide. Oxford.

^ Pizzey, G. and Knight, F. (1997). The Graham Pizzey and Frank Knight Field Guide to the Birds of Australia.

Links and further information: