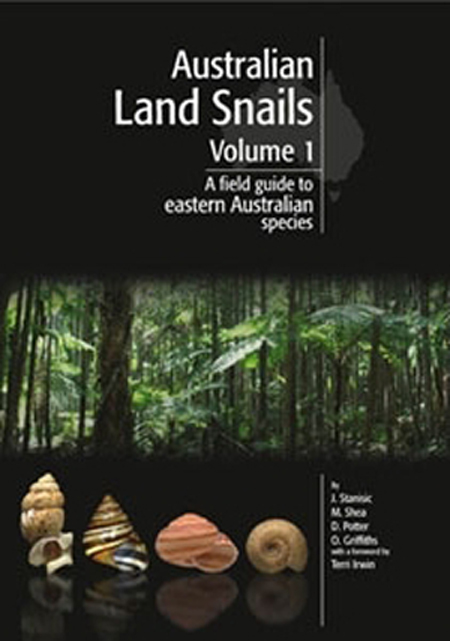

The Jimbour Black Soil Snail (Jimbouria rodhobsoni) — one of 308 new species of land snail described in Australian Land Snails, Volume 1. A Field Guide to Eastern Australian Species, by John Stanisic, Michael Shea, Darryl Potter and Owen Griffiths. The Jimbour Black Soil Snail, named after Rod Hobson from the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS), is found in remnant native grasslands of the Darling Downs, in southern Queensland, Australia. Photograph courtesy of John Stanisic, Queensland Museum.

Having a newly ‘discovered’ species of plant or animal named after you is something that any naturalist would be excited about. While the ‘common’ name for a species may vary over time and from place to place, a scientific name usually remains fixed and unchanging. Consisting of a two-part label (a genus name followed by a species name, in Latin or Greek), a scientific name can tell us something about the species, inform us of that species’ relationship to other species, reflect common names given to the animal by indigenous people or bear the names of people.

In the latter case, the names are often of people who have discovered the species, or who have worked in some related field of biology. This isn’t always the case though — Myrmekiaphila neilyoungi is a species of trapdoor spider described in 2007 by East Carolina University. It is named after Canadian rock musician Neil Young. Cirolana mercuryi is a species of isopod found on coral reefs off Bawe Island, (Zanzibar, Tanzania) in East Africa and named for Freddie Mercury, “arguably Zanzibar’s most famous popular musician and singer”. Agathidium vaderi is a species of beetle named after Star Wars character Darth Vader, while Aegrotocatellus jaggeri is a species of trilobite bearing the name of British musician Mick Jagger (no such honour for Keith Richards, unfortunately). Closer to home, and to the subject of this post, Steve Irwin’s Treesnail, Crikey steveirwini, is a beautifully patterned snail named after the Australian naturalist, educator and conservationist Steve Irwin.

I have several naturalist friends who have already had species named after them — Angus Emmott from out Longreach way (Lerista emmotti — the Noonbah Robust Slider), and Steve Wilson (Strophurus wilsoni — a gecko from Western Australia). Recently, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) colleague Rod Hobson joined them, with a new species of native snail now bearing his distinguished moniker.

The Jimbour Black Soil Snail (Jimbouria rodhobsoni) is one of 308 new species of eastern Australian snail named in a landmark book — Australian Land Snails, Volume 1, by John Stanisic, Michael Shea, Darryl Potter and Owen Griffiths. This book represents thirty years of work, and reflects a lifelong fascination for snails held by John Stanisic, Curator and Biodiversity Scientist at the Queensland Centre for Biodiversity, Queensland Museum.

Representing thirty years of work, this book describes 794 species of land snails from the eastern coast of Australia, as well as Lord Howe and Norfolk Islands. Volume 2 will describe species from the rest of Australia.

There are 44 families of land snail in eastern Australia, with approximately 794 species and 3 sub-species. These misunderstood native animals share an important role in the environment — they are indicators of environmental health, filling niches throughout Australia’s varied ecosystems. They are also fascinating animals, with many having striking and intricately patterned shells.

Land snails are an important group of invertebrate animals that can provide unique insights into the management and conservation of forests. In general, the distribution patterns of Australian land snails reflect the events that have forged the continent’s varied environments, in particular its wetter communities. The close association of land snails with rainforest means they are sensitive indicators of biological change, However, in many instances their existence is under threat. — John Stanisic and Darryl Potter, Wildlife of Greater Brisbane

Found on remnant native grassland on black soils plains in the area around Jimbour, on the Darling Downs, this snail is described as a ‘poorly known but distinctive animal’. It’s appropriate that this snail has been named after Rod, who collected the first specimen of this invertebrate from the Jimbour Town Common in October 2001. Rod has worked extensively on the Darling Downs grasslands — and, like the snail, he’s a distinctive character.

The remnant native grasslands of Jimbour, on the Darling Downs. Only about 1% of this original ecosystem remains intact, and supports a diverse array of plants and animals. Photo Robert Ashdown.

Once covering a vast area, the native grasslands of the Darling Downs have been greatly reduced since European settlement. Today, only about one percent of original grasslands remain — mostly within stock reserves, railway corridors and roadside verges. These remnant native grasslands are one of Queensland’s most endangered ecosystems. The black cracking clay soils that support these grasslands provide refuges and foraging habitat for many creatures, some threatened. It is an ecosystem that needs conservation and careful management.

As a Resource Ranger with QPWS, Rod has worked extensively on fauna surveys and conservation projects on the Darling Downs remnant grasslands. He has collected specimens for the Queensland Museum, and worked with great enthusiasm with locals on many practical conservation projects, such as with the endangered Grassland Earless Dragon. Although Rod hasn’t said much about ‘his’ snail, I’m sure he is excited that this ‘distinctive’ creature will carry his name. I’m also sure he’ll enjoy being part of a special club that includes not only Angus Emmott and Steve Wilson, but a host of other legendary scientists — and also Darth Vader, Neil Young and Mick Jagger! And, he’s a big fan of Keith Richards, so this might be the closest Keith gets to scientific immortality.

[Postscript 11/01/2011. Rod mentions that there are four other newly described species of snails in the book named after highly-regarded naturalist/ecologist friends of his — Adrian Caneris, Craig Eddie, Terry Reis and Mark Sanders.]

[Postscript 25/04/2022. A Guide to the Land Snails of Australia is to be published in July, 2022. For more info see here.]

The shell of the Jimbour Black Soil Snail (Jimbouria rodhobsoni). Photograph courtesy John Stanisic, Queensland Museum.

For more information on snails and the Darling Downs grasslands:

- The Queensland Museum’s snail webpages.

- Saving the boggomoss snail.

- Condamine SQ Landscapes.

- Snail’s Place (Andrew Stafford).

- The Snail Whisperer (John Stanisic).

- John Stanisic’s snail blog.

- A Guide to Land Snails of Australia.

- Snail facts.

Thank God there are people like you and Mr. Hobson around! As far as the grasslands are concerned, I remember as a child growing up with this concept of "wasteland" – in other words, it wasn't being put to any use that could be beneficial to humans; it was wasted. It has taken us a long while to start getting that concept out of our system hasn't it? By the way, I was in Kansas several years ago, and were given a talk about the importance of the different kinds of endangered grasses on the prairie, and how they needed to be preserved as they supported important ecosystems. As for snails, I am always fascinated by the Jamaican ones I find in the garden, though I know very little about them. I must take a couple of pictures and share them with you. Thanks for this amazing blog (I am still pondering how a trapdoor spider came to be named after one of my favorite old rockers, Neil Young!)

I'm consistenrly amazed by your story and others from around the world about eco/abuse. The area I live in was almost destroyed by mining and smelting. This AM on the news a couple in Sask. is suing about CO2 comtamination of their farm. Next door is an oil field where the oil is forced out by using excess CO2 and hoping that it will stay underground.A local science authority reported that the CO2 is definitely from the oil field The company spokeswomen said their system is safe ( probably like cigarettes) and the Premier of the province said he had no evidence, so the system goes on. I don't need to mention the tar sands where the premire of that province thinks everything is fine. But ducks still land on contaminated tailing ponds and near-by aborginals have high incidences of cancer. The point is we always wake up too late. Gary of the Vermilon River, Canada.

Robert, I really enjoyed reading the blog article about Jimbour, the wide road reserve, and the land snails. The Dalby-Jimbour road reserve is a constant worry for myself. I wonder just how long it will be able to survive in this modern age, before additional pipelines are ripped through it and the road is increased by another lane or two. I generally find that instead of sacrificing the narrowest side of a road reserve, planners always seem to want to take the widest part. It is almost as if our developers and engineers are still living in the days of the "wild West" where they assume everything in the country is vast and endless and there will always be plenty of room to go around. I have in fact travelled to remnant grasslands of the Darling Downs with environmental consultants who clearly grew up in a big city environment. Their perception is often very skewed and subjective to say the least! Often their first remark is just how big, flat, and boring (yes "boring"- their words not mine!) the landscape and ecology is. I could often tell that they felt really let down having to do a job in such a dry, hot, flat, and "dreary" place, when at university they had aspired for assignments close to the beach, the suburbs, or in a montane rainforest. In reality, the grassland habitat often houses a remarkable diversity of life, on par even with places like the Great Barrier Reef. It just takes a careful eye to look and see it. Once people do start to look, their perceptions of grasslands will never be the same.

Your estimation of 1% remaining of the original grasslands really brings home the reality of the matter. What at first seems large is actually quite small. Factor in the following and we soon see that the actual figure is much less: constant weed invasion from road edges and neighbouring farmland; inappropriate drainage from farmland sending chemical and fertilizer laden run-off into remnant grasslands; spray drift from cropping activities; surface scraping & the construction of diversion lanes during roadworks; deep ripping of drainage lines & dumping of weed-infested overburden into stockpiles; also the construction of multiple access roads by local farmers (which often run parallel with cultivated land, thus reducing the width of the reserve markedly); inappropriate tree plantings and slashing regimes; lack of proper fire management… the list goes on.