It’s a mid-winter night in Toowoomba, raining and cold. I step outside and my bare foot squishes something cold — cold, but very much alive.

The Red Triangle Slug (Triboniophorus graeffei), an air-breathing native slug. Photo R. Ashdown.

Oh no! I’ve trodden on a favourite invertebrate, one of a host of unusual creatures that come out to play in the suburbs at night. It’s a Red Triangle Slug — creator of the strange rows of circular marks covering fences and trees throughout town. It’s a wonderful wet night, perfect for them to rampage about the backyard.

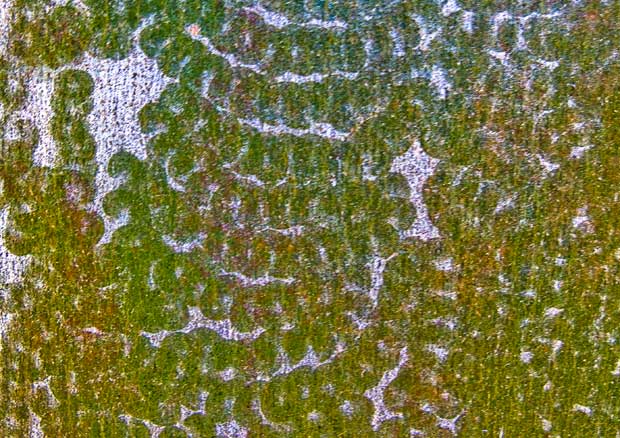

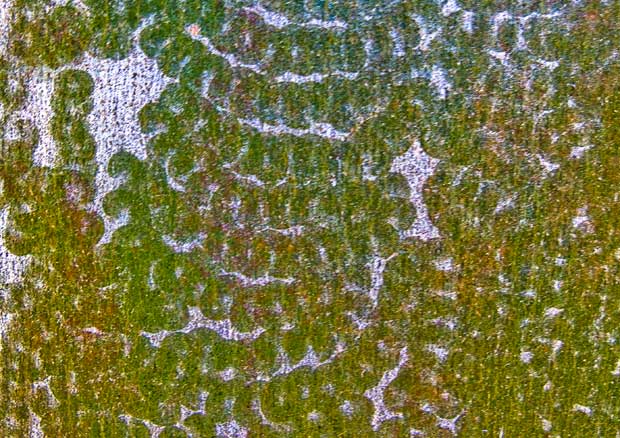

The grazing marks of Red Triangle Slugs on a Toowoomba fence. Photo R. Ashdown.

These colourful native animals are one of approximately 1,500 species of land snails and slugs found across eastern Australia, a number that includes both native and introduced species. Most of the slugs and snails found throughout the gardens of towns such as this one are introduced, as native species have not coped well with the changes that urbanisation have brought to their original habitat. Red Triangle slugs, however, are an exception — survivors and adaptors, turning up all over the place.

A Red Triangle Slug in rainforest at Ravensbourne National Park. Photo R. Ashdown.

What type of creature are these Red Triangle Slugs, named for the … well, red triangle … on their backs? They are “terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs from the family Athoracorphoridae”, the leaf-veined slugs.

Molluscs are soft-bodied invertebrates that usually have a shell for protection from human toes and other problems. They have a ventral foot for locomotion and, in aquatic species, gills for respiration. Their digestive and reproductive tissues are located together to form a visceral mass inside their bodies. An extensive fold of tissue, known as a mantle, covers them and is a protective sleeve for the head and gills. In snails it produces the shell. In the Triangle Slugs, it is reduced to the red-bordered patch on their backs.

Slugs and snails belong to the class of molluscs known as gastropods, which includes marine, freshwater and land snails (mostly with coiled shells) and slugs (without shells).

The eyes have it. Simple eyes, on tentacles. Optical tentacles, if you like. Slugs can only ‘see’ light and dark, and the eyes are not able to focus. Photo R. Ashdown.

Growing to a length of 14 cm, the Red Triangle Slug is One of Australia’s largest native slugs. Found in coastal forests (and some towns) from around Wollongong New South Wales north to Mossman in northern Queensland, they graze on the microscopic algae that grow on tree bark, footpaths, posts and fences, among other things. Naturalist Martyn Robinson discovered that if given the chance these slugs will also remove bathroom mould!

The circular feeding marks of Red Triangle Slugs on a Spotted Gum. Photo R. Ashdown.

Late afternoon on a dark, wet day. A Triangle Slug roams a Camphor Laurel next to the Clive Berghoffer Stadium. Photo R. Ashdown.

Alas, our stairs are in poor shape. Any remains of paint have been replaced by algae. Perfect, however, for a rampaging slug looking for a feast. Photo R. Ashdown.

Doesn’t say much for the state of the back-door’s glass either! This slug runs amok in search of algae, or seeks a view of what the humans get up to at night. Photo R. Ashdown.

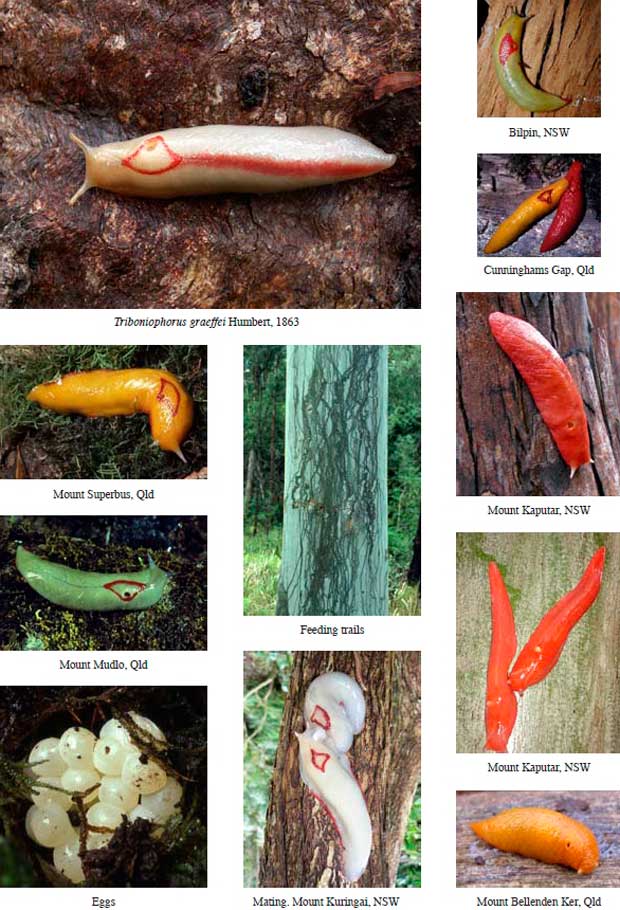

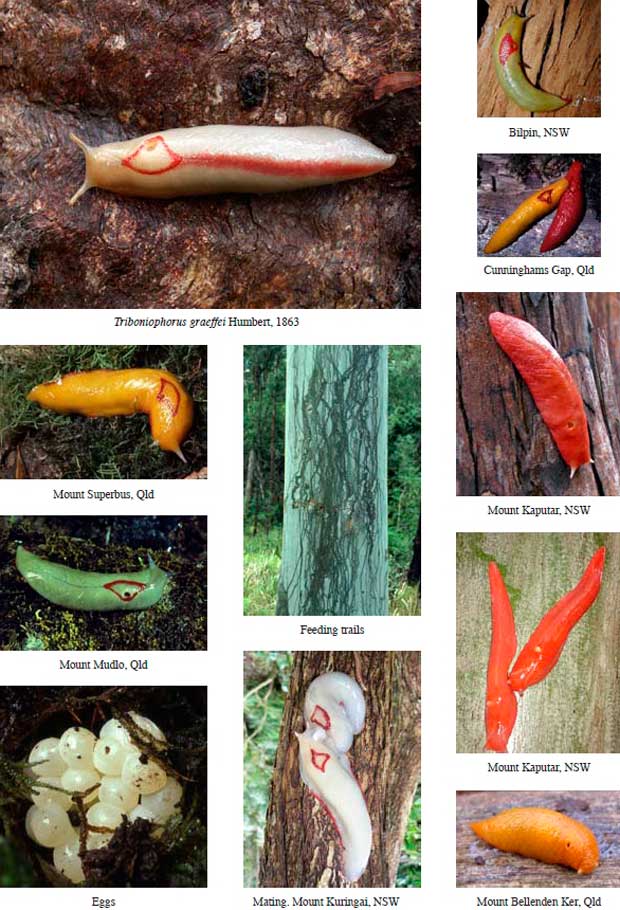

Red-triangle Slugs come in different colours. While the most common colour form is a creamy white animal with a prominent red triangular mantle shield, all-red and all-yellow animals can be found at Cunninghams Gap (south of Toowoomba). Future molecular studies may reveal that some of these colour forms are actually distinct species.

An orange form of the Red Triangle Slug, at Mt Mitchell NP, Cunninghams Gap. The hole inside the red triangle is the animal’s respiratory opening, known as a pneumostome, or breathing pore. This is a feature of all air-breathing land slugs and snails. Photo Harry Ashdown.

Photographing a Red Triangle Slug, Mt Mitchell, Cunninghams Gap. Photo R. Ashdown.

Toowoomba resident Jane alerted me to the presence of a beautiful red form of the slug in her Toowoomba backyard. Here are several curled up in a log in her great garden. Photo R. Ashdown.

Colour variations in Red Triangle Slugs, from Australian Land Snails, Volume 1, by John Stanisic, Michael Shea, Darryl Potter and Owen Griffiths — gastropod gurus! Courtesy Darryl Potter.

If you have read this far you are probably not the kind of person who finds slugs disgusting. So, I don’t need to finish this post with a monologue about the important role native slugs and snails play in our ecosystems, as they go about recycling nutrients and offering themselves up as (sticky) food for many other critters.

I’ll just end by saying that it’s always great to see these little slow-motion beasties on wet nights, but not so great to feel them between your toes!

A Red Triangle Slug motors slowly along the footpath outside our place near midnight as cars swish past. A splash of colour on a drab, dark night in the ‘burbs. Photo R. Ashdown.

Slugs on the web: