Most working days I walk through Queens Park on my way to and from town, passing a beautiful Queensland Bottle Tree (Brachychiton rupestris).

I ended 2012 by taking some extended leave, and each morning I walked the little black dog through the park, gradually slowing down and looking around instead of rushing to work.

I ended 2012 by taking some extended leave, and each morning I walked the little black dog through the park, gradually slowing down and looking around instead of rushing to work.

While I’m a bigger fan of wild areas, there are always things to discover in parks. The more I looked at this tree, the more I saw and liked. Walkers, dogs, joggers ands cyclists pass directly under its canopy, lost in their thoughts and usually oblivious to its charms.

Over the next three months I kept looking, photographing it with whatever I had on hand. Not knowing anything about Brachychitons I was concerned when it shed most of its leaves in the hot, dry October/November weeks, thinking it was drought stressed.

A carpet of dead leaves during dry summer months. All photos R. Ashdown.

However, a bloom of new orange and pink foliage belayed my fears. I found out later that this is a characteristic of these trees — they often do this before flowering, and they can also shed leaves to conserve moisture during prolonged drought.

Queensland Bottle Trees often shed their leaves before flowering, or during drought times. New growth is a beautiful pink colour.

Good to see I’m not the only one admiring this tree.

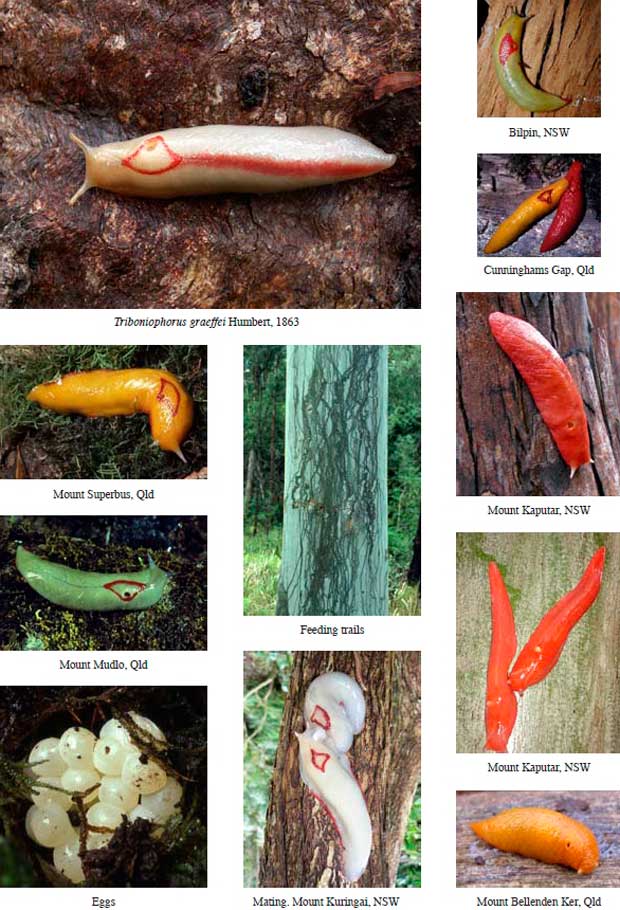

Also known as the Narrow-leaved Bottle Tree, this is one of 31 species of Brachychiton, with 30 found in Australia and one species in New Guinea. The common name “bottle tree” refers to the characteristic trunk of the tree, which can reach up to seven metres in circumference. Fossils from New South Wales and New Zealand have been dated at 50 million years old.

Pale-headed Rosellas seem to enjoy chewing the bark of bottle trees. A pair regularly hang out quietly in the tree.

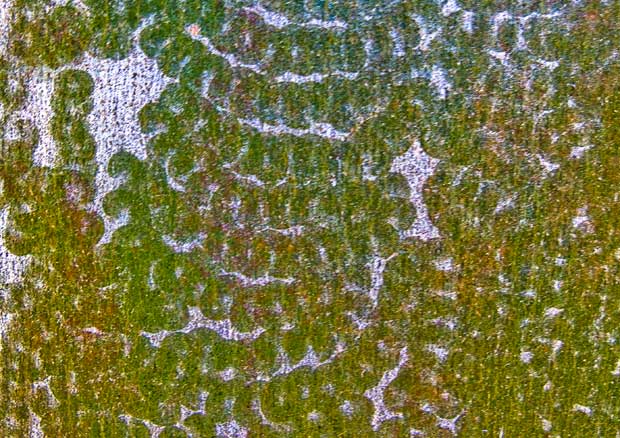

The tree supports a mosaic of lichens, usually very pale and hard to see during dry times.

Midday, and bloody hot! A distinguishing feature of this particular tree is a water-mark that runs down one side. These trees do not store reservoirs of water, but their interior is made of a spongy, fibrous material that holds moisture. Photo by Harry Ashdown.

Sometimes, despite there being no rain for days, moisture seeps down the water-mark. Maybe early morning condensation moving down branches?

Rain at last — summer thunderstorms appear in December 2012.

Workers return home through welcome rain …

… while, soaked with water and lit by the twilight, the tree glows quietly.

A dark, rain-soaked trunk sports subtle hues …

… and the lichens seem to spring outward.

Before long we are back to long, searing days again in January 2013’s record heat wave.

Queensland Bottle Trees are endemic to a limited region of Australia — Central Queensland through to northern New South Wales. In 1845 the explorer Thomas Mitchell led an expedition seeking an overland route from Sydney to the Gulf of Carpentaria. He ran into these trees on his journey, within the brigalow (Acacia harpophylla) scrub that covered much of central Queensland. Mitchell found some trees so wide that a horse standing side on was said to disappear from view. This tree would be the saviour of many early squatters.

A name-carved bottle tree has witnessed families come and go in Central Queensland.

The Bottle Tree’s most striking characteristic was that its trunk was not made of sapwood like ordinary trees, but rather consisted of a spongy fibre, which was also filled with moisture. In times of drought, settlers would cut down bottle trees and peel off the bark — exposing the fleshy fibre, which cattle would eat. A large tree could satisfy a hungry, thirsty herd for weeks.

Indigenous peoples of course knew the value of this tree, carving holes into the soft bark to create reservoir-like structures, and the seeds, roots, stems, and bark have all been a source of food for people and animals alike long before white settlers arrived. The fibrous inner bark was used to make twine or rope and even woven together to make fishing nets.

The strange, spongy bark of a Queensland Bottle Tree.

Bottle tree seed-pods, Auburn River National Park. This is a close-relative, the Broad-leaved Bottle Tree (Brachychiton australis).

Seed-pods of Brachychiton australis. Photo courtesy Vanessa Ryan.

Deemed a ‘useful’ tree, bottle trees were often left by settlers when they were clearing land. Today, solitary specimens are often seen in fields. To me they are reminders of times not so long ago when vast areas of central Queensland were covered in scrub.

Near Proston, Central Queensland. A hill once covered in ‘softwood scrub’.

Farmlands and remnant bottle trees, Roma.

Roma, central Queensland.

In the brigalow-dominated landscape of the Queensland bio-region known as the Brigalow Belt, Queensland Bottle Trees were found within pockets of ‘softwood scrub’ — or ‘semi-evergreen vine thicket’, a type of scrubby, dry rainforest. These ecosystems show some of the characteristics associated with the wetter tropical type of rainforest but are less luxuriant, lacking species such as tree ferns, palms and epiphytes. They also have a reduced canopy height and are simpler in structure.

A Brachychiton stands out amongst the silver foliage of Brigalow (Acacia harpophylla). Arcadia Valley, central Queensland.

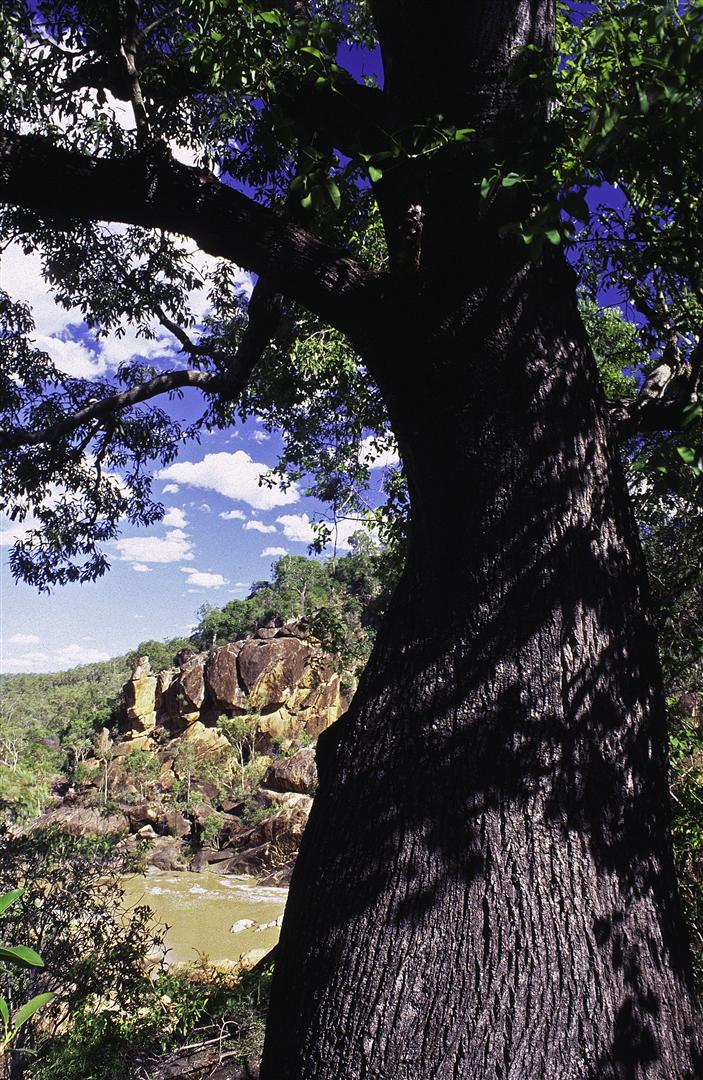

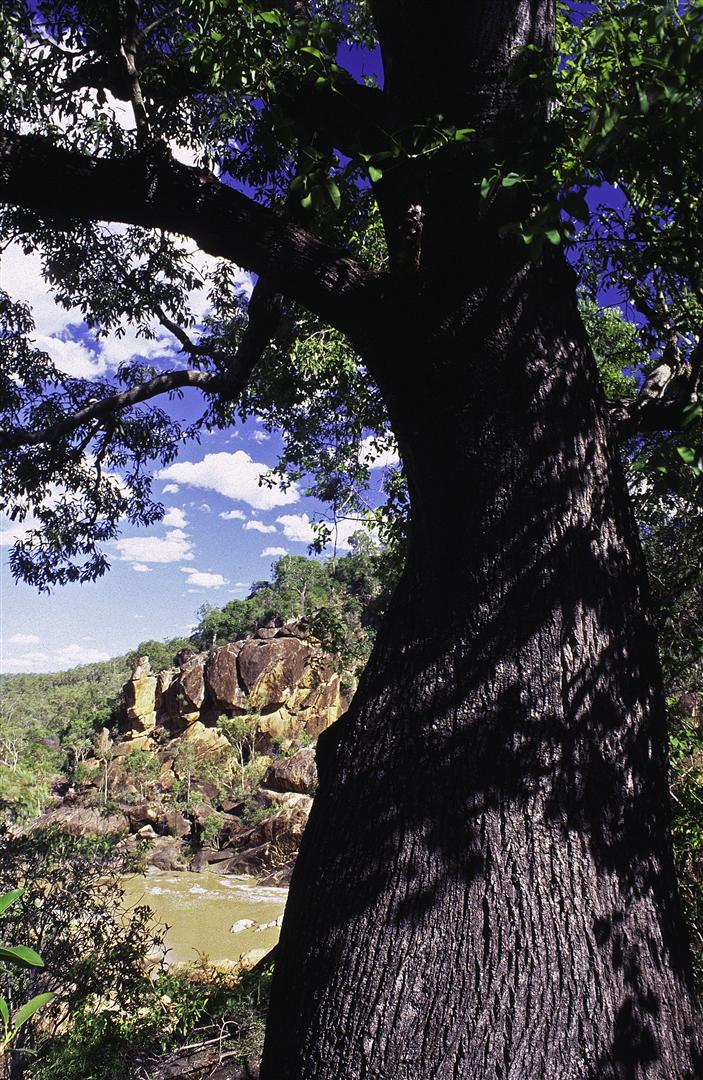

Queensland Bottle Trees are lit by the afternoon sun within remnant softwood scrub, Auburn River National Park.

Down at ground level within softwood scrub at Isla Gorge National Park (the trunk of a bottle tree is on the right). The technical term for these scrubs is ‘semi-evergreen vine thicket’.

Adaptations found in these forests to drier environments include smaller, thicker leaves, swollen roots and stems, and an (optional) deciduous habit — meaning that plants can preserve moisture by losing their leaves in times of extreme drought.

Auburn River National Park. A Queensland Bottle Tree stands over the flooded river, 2004.

The same location — a Broad-leaved Bottle Tree in its original habitat. A tad wilder, and a lot more interesting, than Queens Park.

Since white settlement approximately 83 percent of this type of ecosystem has been cleared, and the remaining patches are classified as endangered ecological communities.

About 20 percent of the remaining patches are found in protected areas, such as Cania Gorge, Carnarvon, Bunya Mountains and Expedition national parks. I’ve spent some magic hours walking within these remaining patches of softwood scrub, and it’s always exciting to come across a large bottle tree within its original habitat.

A mighty specimen reaches high above cleared farmland in central Queensland.

Bottle Trees are also sought-after ornamentals, and line the streets of towns from Brisbane to Roma.

Queensland Bottle Tree, Brisbane (thanks, Susan).

Queensland Bottle Tree, Anzac Square, Brisbane. Photo courtesy Vanessa Ryan.

My solitary Queens Park tree, looking down onto Toowoomba’s central business district, seems odd and out of place to me in this cultivated landscape — a strange, silent, and somewhat troubling reminder of wild times past, when tangles of un-tamed vine scrub ruled much of the land now civilised and ordered by farms and towns.

January 27, 2013. Ex-tropical cyclone Oswald works its way down the east coast, bringing heavy rain and winds, and soaking ground for thirsty trees.

Next day. The rain and wind has gone, the ground is soaked, shadows are back with the afternoon sun.

Water still soaks down the tree’s side.

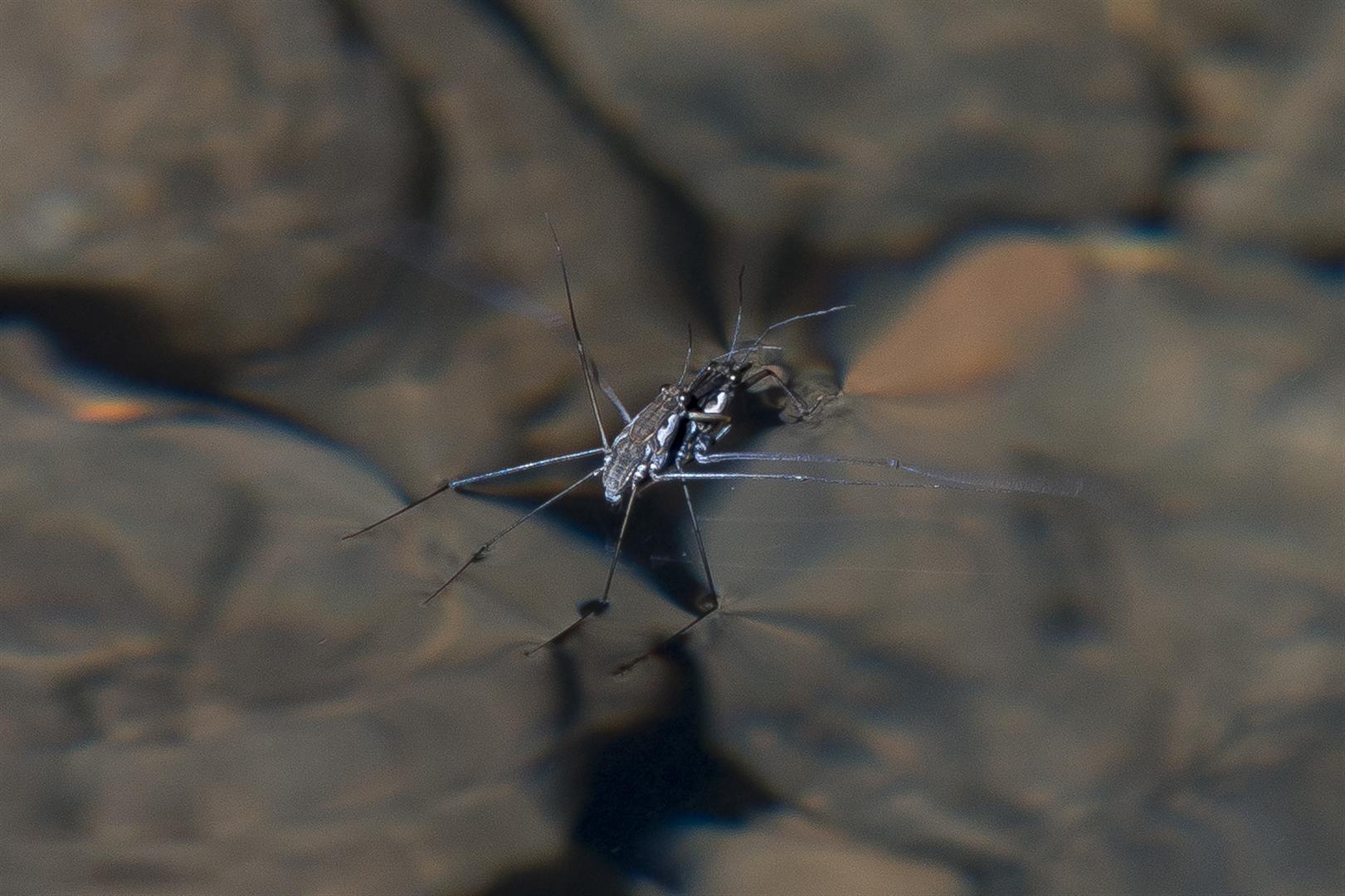

A millipede enjoys the water.