The Simpson Desert. All photos in this post by Robert Ashdown.

The scene was awfully fearful, dear Charlotte. A kind of dread (and I am not subject to such feelings) came over me as I gazed upon it. It looked like the entrance into Hell.

[Explorer Charles Sturt on encountering the edge of the Simpson Desert, September 1845.]

In 1996 I spent some time on the edge of the Simpson Desert. Not much time, and not far into the desert, but it was a memorable adventure.

As an image I’d taken on that trip was recently chosen for the cover of a book on macroevolution (the evolutionary and ecological processes responsible for generating patterns of biodiversity), it seemed like a good opportunity to post some slide scans, accompanied by a few words written for an article published in the Summer 1996 edition of Wildlife Australia.

The Simpson Desert. To some the name may conjure images of lifeless sand dunes, of a stark and deadly landscape. To visiting naturalists, the Simpson is a place of subtlety, surprises, life, colour and great contrasts.

The Simpson Desert covers part of three states at the arid centre of Australia. More than 1,000 parallel sand ridges, often running unbroken for great distances, form a unique landscape. It is one of the world’s great sandy deserts.

Lobed Spinifex (Triodia basedowii) forms hummocks on dune crests. It provides refuge for many species of desert fauna.

Central Military Dragon (Ctenophorus isolepis).

Aboriginal people lived in this desert for countless generations, basing their lives around wells and an intimate contact with the desert plants and animals. Early Europeans saw it as a dead zone — devoid of flora and fauna of any real value.

The Desert Grevillea (Grevillea juncifolia) is one of the many desert plants that can survive long periods without rain. I watched Black Honeyeaters coming over the sand ridges to land in them for a brief nectar refuel.

These notions faded as expeditions and surveys revealed an astonishing biodiversity. Far from being a monotonous and lifeless wasteland, the Simpson Desert encompasses a variety of constantly changing land-forms, each providing habitat for many superbly adapted plants and animals. New and exciting biological discoveries are continually being made.

To the visiting photographer, the Simpson is overwhelming. The vast, silent landscapes do not easily reveal their secrets. In a dry creek bed between sand ridges, we share the midday shade with a host of birds.

The dry bed of Gnallan-a-gea Creek, Simpson Desert.

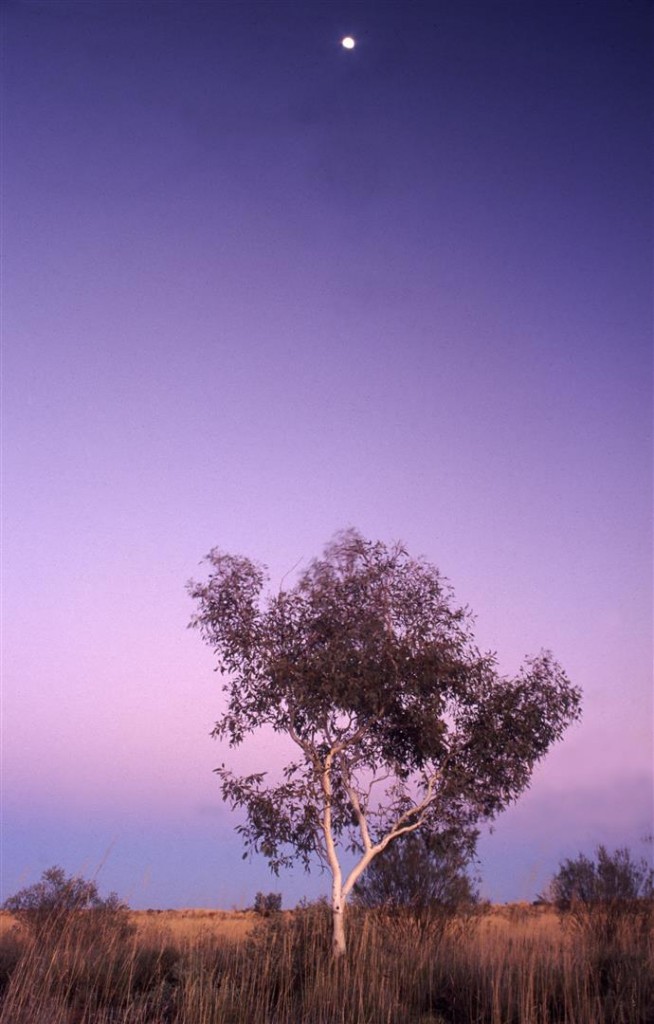

The change from afternoon into night is soft and magical. As the sun sinks, the red sand on the ridges glows with a luminous intensity. The shadows of the wildflowers and other plants lengthen.

Silence returns and cloaks everything with a palpable intensity, The dome of the sky sweeps down to invade the ground as the twilight colours fade and the horizon vanishes, Another day in this remarkable place has ended.

Gillens Moniter (Varanus gilleni), a species of small goanna. We found wandering about the creek bed at night.

And who ended up on the cover of that book? A character I’d been hoping to meet.