The Death Adder is one of Australia’s more unusual snakes. This post presents some recent photos of this reptile from around Queensland and northern New South Wales.

Maree Cali from Mackay spotted one of these highly venomous elapids close to her campsite. Says Maree, “I was excited to accidentally set up camp over the Easter break next to this cool customer and was blown away by its laid back nature, camouflaging ability and beauty — and I’m not particularly into snakes.”

Gerry Swan and Steve Wilson give an overview of Death Adders in their book What Snake Is That?

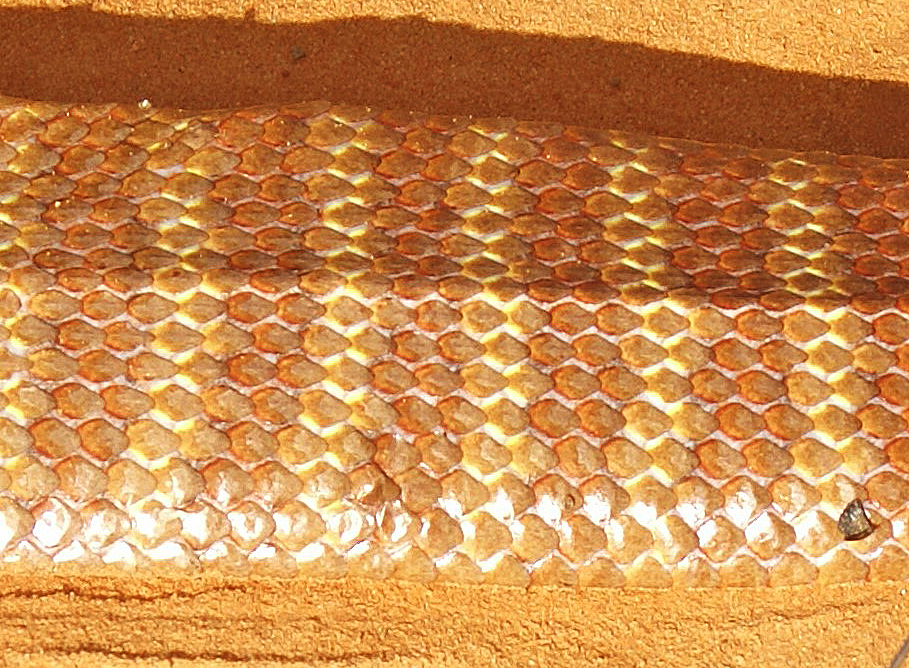

Australia is the only continent with no vipers, family Viperidae. In their absence, some elapid snakes of the genus Acanthophis have evolved to fill a similar niche. These sluggish, well-camouflaged and sedentary snakes lie concealed in leaf litter or under low shrubs and grasses. Important features of this group are a short, thick body, a broad head distinct from the neck and an abruptly slender tail.

Their similarity to vipers was not lost on early settlers, who were reminded of the Adder (Vipera berus) from Britain and Europe. They named the Australian snakes ‘death adders’ because of the high mortality from bites before anti-venom became available. The corruption ‘deaf adders’ may derive from their reluctance to move away when disturbed.

Death Adders are ambush predators that feed on a variety of vertebrates. The slender tail has a segmented tip and soft spine, and they lie with this resting near the head, When prey is detected, the snake wriggles the tail convulsively, mimicking a grub or worm to lure the animal within striking distance. Its ability to strike so suddenly and with such mind-boggling speed is unnerving to witness, particularly considering the snake is slow moving and prone to lie motionless for days on end. The strike is accurate and lethal, as a powerful venom is injected deeply through long fangs.

Death Adder, with strikingly patterned head strategically positioned near its tail (aka caudal lure!). Captive specimen, photograph R. Ashdown.

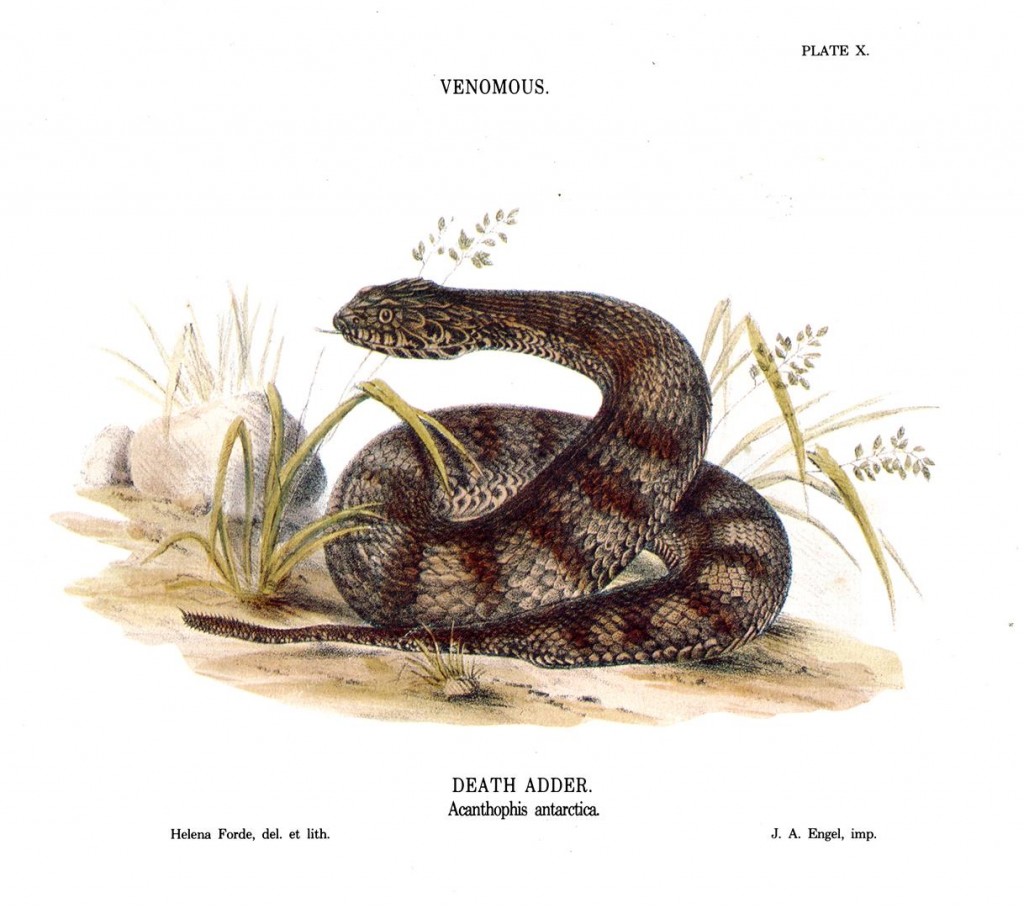

Common Death Adder. From The Snakes of Australia, by Gerard Krefft, 1869. Death Adders are not true ‘adders’, belonging instead to the same family as other venomous Australian snakes, the elapids. Their similarity to adders, which are actually members of the viper family, has evolved in response to the species’ environment and their ‘sit and wait’ style of life, which does not require a snake to be long and agile but short and muscular for a quick strike when necessary.

Kate Steel encountered a Death Adder near her back verandah of her house in northern New South Wales. Kate relocated the snake in a sack, grabbing a few photos on the way. She posted on Facebook, “Just caught this slithery under the verandah, there was a Willy Wagtail giving warning and then Lyly the alarm dog. Hope the photos are not too shaky cos my hand is!”

A Death Adder being relocated from near the back verandah to somewhere less likely to be trodden on by bare feet. Photo by Kate Steel.

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) Rangers often encounter snakes as part of their daily work. Ranger Stuart Fyfe took the following photos of a Northern Death Adder (Acanthophis praelongus) in far northern Queensland.

“I found this Death Adder pretty late one night outside the barracks common room, (around 11pm), so took a few photos then put him in a bucket to relocate him in the morning. We have a couple of families on base with small kids, so we tend to relocate these guys down the track.

When I first found him he was quite docile, and didn’t puff up even when I put him in the bucket, but when I released him in the morning he was all fired up — they tend to puff up like that when they are being defensive. He must not have liked being in the bucket overnight.”

Death Adder moving out of grass to escape a controlled burn on national park. “This was one of the biggest we’ve seen up here. Based on the width of the Rake Hoe I estimate he was about 42cm long.” — Stuart Fyfe. Photo by David Delahoy, QPWS.

How dangerous are death adders to humans? From a Wikipedia article that lists details of deaths due to ‘unprovoked bites by snakes’ in Australia:

The estimated incidence of snakebites annually in Australia is between 3 and 18 per 100,000 with an average mortality rate of 0.03 per 100,000 per year. Between 1979 and 1998 there were 53 deaths from snakes, according to data obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Between 1942 and 1950 there were 56 deaths from snakebite recorded in Australia. Of 28 deaths in the 1945-49 period, 18 occurred in Queensland, 6 in New South Wales, 3 in Western Australia and 1 in Tasmania. The majority of snake bites occur when people handle snakes in an attempt to relocate or kill them.

Australia is the only continent where venomous snakes constitute the majority of species. Snake bites in Australia that cause deaths are less common than they once were, because of increased medical knowledge and anti-venom that is better and more available. Around half of all deaths from snakebites are thought to be caused by brown snakes, perhaps as many as 60% of deaths caused by snakebite.

Unlike other snakes that flee from approaching humans crashing through the undergrowth, common death adders are more likely to sit tight and risk being stepped on, making them potentially more dangerous to the unwary bushwalker.

However, they are reported to be reluctant to bite. Richard Shine, in Australian Snakes, a Natural History, describes this apparent reticence:

There are many stories testifying to this docility, perhaps the most famous being of two men cutting sugarcane in a paddock. They spent the day working at the job, carrying loads of the crop frequently out of the gate to their nearby truck. It was late in the day that one of the workers noticed a large Death Adder coiled in the dust in the middle of the path, right beside the gate, The dust showed hundreds of footprints from their bare feet within a few centimetres of the snake’s head.

Ranger Andrew Young recalls a family Death Adder encounter when he was a lad growing up on the family farm at Stanwell, west of Rockhampton, in the 1960s. He remembers lots of yelling, and dancing about, associated with this particular snake sighting.

“My Dad had sent the farm-hand out to our other property at Ridgelands where he was to plough up some paddocks for planting sorghum. When he was finished he drove the tractor back to our Stanwell farm for some more work we had there. The farms were about 40 minutes drive apart by car so a good couple of hours by tractor.

When he arrived home that evening we all went to meet him and hear how he went. During the discussion, he said, “Oh, and I found a great legless lizard today!” He opened the tool box on the side of the tractor and hauled out this Death Adder! Dad shouted “Drop it!” and we all leapt back — as you might imagine! I shall not recount the snake’s fate …

But I have always thought that the snake was indeed laid back as it didn’t bite when it was ploughed out of the soil nor when grabbed out of the tool box that it had been jiggling around in all day.”

In its element. A Death Adder photographed in the Mount Moffatt section of Carnarvon National Park by QPWS Ranger Brent Tangey.

Many bites from Death Adders proved fatal before the introduction of antivenom. Death Adder venom contains a type of neurotoxin which causes loss of motor and sensory function, including respiration, which can result in paralysis and death. Deaths from bites are still common in New Guinea.

How dangerous are humans to death adders in Australia? In reality, this snake is perhaps more endangered than dangerous. Despite being labelled ‘common’, the Common Death Adder is becoming increasingly less so. Gerry Swan and Steve Wilson write:

Death Adders have declined in many areas. They can be regarded as biological indicators of environmental quality as they appear extremely susceptible to degraded conditions. Weeds, altered fire regimes, introduced predators and toxic prey in the form of the introduced Cane Toad all play a part in the demise of these snakes from sites where they were once extremely common.

As Steve, who has pursued reptiles across the continent for decades, said to me when talking about Common Death Adders, “I defy anyone to call them ‘common’.”

Reptiles are beautiful and fascinating creatures. They are a fundamental part of Australia’s wonderful biodiversity — something that is under constant siege. Says Steve:

The loss of native vegetation has been the most substantial and urgent problem facing Queensland’s reptiles and other fauna. The estimated annual toll from broad-scale clearing between 1997 and 1999 was a staggering 89 million reptiles, a figure no doubt matched today as hundreds of thousands of the state’s extraordinarily complex natural heritage is bulldozed, heaped and burnt. Apart from the immediate individual casualties, the loss and fragmentation of habitat has implications at population and species levels. With the spectre of increased clearing for expanding coal and gas exports and the push for more northern development, it is critical that habitat continuity be prioritised.

I’m yet to encounter one of these snakes in the wild, but hope the chance to do so will be there for a while yet.

There are five currently recognised species of Death Adder found in Queensland, though several distinct populations may prove to be valid new species. Between these species, Death Adders can be found over most of mainland Australia, except Victoria. All are live bearers, with litters of over 30 young recorded. This is a Northern Death Adder (Acanthophis praelongus). Photographer Greg Watson photographed this captive specimen at Kuranda (within the species’ range and of an animal with a size and the pattern consistent with the location).

Common Death Adder (Acanthophis antarcticus). Photographed on a QPWS fauna survey of Bringalily State Forest by Bruce Thomson

A strikingly patterned Common Death Adder from central Queensland. Photo by Steve K Wilson.

For more information on the five Death Adder species found in Queensland, see A Field Guide to Reptiles of Queensland (second edition) by Steve K Wilson. The book contains some beautiful images of these snakes by Steve and fellow reptile photographers Angus Emmott and Gary Stephenson.

[Safety note: Death Adders are dangerously venomous. All photos on this post were taken at a safe distance. It’s not a good idea to test a Death Adder’s mood by touching one or getting too close with a camera. Seek professional assistance in relocating a snake if you need to move one.]

Thanks to:

- Greg Watson (gregwatsonphotography.com.au)

- Bruce Thomson (www.auswildlife.com)

- Maree Cali

- Stuart Fyfe

- Brent Tangey

- Kate Steel

- Andrew Young

- Rennie Fletcher

- David Delahoy

- Steve K Wilson (www.stevekwilsonreptiles.com.au)

I’ve seen plenty of venomous snakes over the years but haven’t noticed adders yet. I’ve probably almost stood on them without even noticing though! They can be very well camouflaged and still. Great post, Rob! We hear a lot about Browns and Taipans but not so much about adders. Thanks for enlightening us.

At sun-up, checking the wheelie bins I looked down and saw my foot about 10cm from the coiled snake. I stepped back; sais “Sorry about that”. And the snake uncoiled and calmly went behind the bins. I went indoors quite relieved that I had not trodden on it!