The story of mistletoe mutualisms is about entanglements of interdependencies, nutrient cycles, and seductions. It tells of an ethos of giving that goes around and comes back, producing entanglements that are veritable orgies of seductive gifts. — Deborah Bird Rose

Mention mistletoe and the inexplicable Christmas tradition of kissing under one might be the only response. That is, getting friendly in the snow under a northern-hemisphere plant (a species of Viscum), which most have probably never seen.

European mistletoe (Viscum album), from the family Santalaceae. It is native to Europe as well as to western and southern Asia. A plant with a significant role in European mythology, legends, and customs. In modern times, it is commonly featured among Christmas decorations and symbology. Long used in alternative medicine traditions without any scientific basis, mistletoe now is under study for pharmaceutical uses in modern medicine. Photo by Sarkolot, Pixelbay.

The whole mistletoe/Christmas connection predates Christianity, with mistletoe featuring prominently in the Druid’s ancient winter solstice rituals. With their bright green leaves and complete absence of roots, mistletoes are especially apparent on leafless hosts in the winter, and these sprigs of green in an otherwise lifeless forest inspired a rich folklore. Having harvested a mistletoe sprig from an oak with a golden sickle, the cutting was taken back to their temple where it was kept for three days. On the fourth day (Christmas Day), the leaves were distributed to worshippers, signifying the rebirth of the sun and ensuring a bountiful harvest in the coming season. Variations of these rites are still practised today. Mistletoe sprigs variously deter trolls from stables (Sweden), prevent nightmares (Austria), welcome loved ones home (Heathrow airport in London), or give a sharp-eyed colleague kissing privileges at the staff party. — David Watson

We have our own mistletoe, with at least 93 species (from two families) found in Australia. Mistletoe has a long-held reputation here as a pest and a parasite, an evil thing that kills trees. How accurate is this? It would seem that the truth about these plants is fascinating, mysterious and complex.

In their field guide on mistletoe, John T Moss and Ross Kendall wrote, “An aura of mystery surrounds mistletoes. In Australia, they are not well known and are probably one of the most misunderstood of plant groups … where dominant eucalypts host large and spectacular pendulous mistletoes, the killer mistletoe myth has persisted for over a century. But a parasite killing its host does not make sense as it would also die! Why would a native mistletoe kill a native tree? In fact, mistletoes use photosynthesis to manufacture their own carbohydrates (including sugars and cellulose). They also manufacture hormones and other compounds as required for their growth and may in fact contribute some compounds back to their hosts. Thus, far from the common misconception that mistletoe are destructive parasites, they are, in fact, in equilibrium with their hosts.”

I have always enjoyed seeing and photographing mistletoe, and as I’ve encountered more species, in diverse places, my appreciation of their aesthetic appeal and fascinating role in Australian ecosystems has grown. Read on, for the inside story on these mysterious plants.

Gruesome and totally revelatory, the mistletoe story. — Ross D McKinnon AM (Retired Curator-in-Charge, Brisbane Botanic Gardens), in his foreword to ‘The Mistletoes of Subtropical Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria’, by John T. Moss and Ross Kendall.

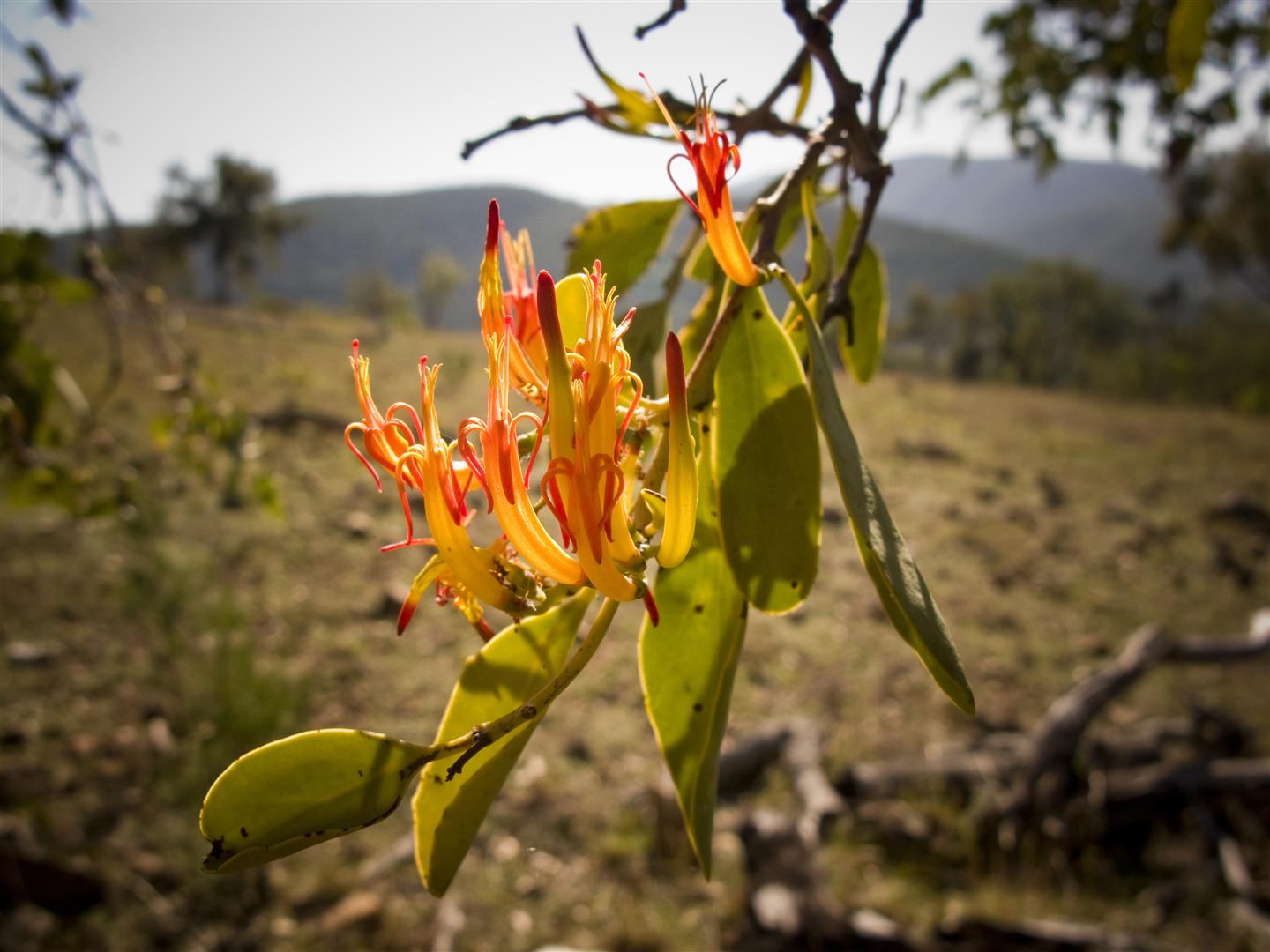

Mistletoe flowers (seen here in a eucalypt at Yelarbon State Forest), are a colourful feature of Australian woodlands. Photo R. Ashdown.

The mistletoe, as Australian as the gum tree

Rod Hobson

This may come as a surprise to many but contrary to popular belief mistletoes are not parasites. Botanists regard mistletoes as ‘hemi-parasites’, that is ‘half-way parasites’. Biologically, a parasite is an organism living in or on another organism (its host) from which the parasite obtains its food. Mistletoes don’t take anything from their host other than sap water and any minerals therein. They have green leaves therefore they have chlorophyll, which means that they are fully photosynthetic and process all their own food. During long droughts mistletoes suffer severely, as they don’t have any of the various means to conserve water that their hosts might possess. This is especially so if the survival strategy of the host includes restricting water flow to its outer branches. This process thus ‘starves’ the mistletoe of this essential commodity and the mistletoe may eventually succumb to this tactic.

The orange of mistletoe stands out against the green of eucalypts at Sundown National Park. Photo R. Ashdown.

Harlequin Mistletoe (Lysiana exocarpitenuis). Mistletoes not only provide food for many native animals, birds and insects but are also a source of shelter and nesting sites for many species. Several types of honeyeater including wattlebirds and friarbirds have been recorded nesting in mistletoe clumps. There is even a record of the secretive Grey Goshawk (Accipiter novaehollandiae) nesting in mistletoe. Many birds such as the Mistletoebird, cuckoo-shrikes, ravens and crows, cockatoos, shrike-thrushes, woodswallows, bowerbirds, even Cassowaries and Emus have been observed eating mistletoe. Photo Craig Eddie.

Another popular belief is that mistletoes kill trees. This is not so, as it would take a great many mistletoes to kill a tree and many large trees can be seen doing quite well despite their heavy load of mistletoes. A large number of mistletoes on a tree could well contribute to its decline if the tree was under stress from other factors such as adverse climatic conditions, disease or heavy insect attack. The outer parts of a mistletoe-infected branch will often die though, as upon germination the mistletoe’s anchor (haustorium) enters the water-carrying section (xylem) of its host. Eventually the haustorium may totally block the xylem thereby ‘starving’ the branch’s extremities of water and causing their deaths.

Many Australian mistletoes are specific to one or a few host plants. This Brush Mistletoe (Amylotheca dictyophleba), however, is found on several native rainforest and mixed forest trees. It has also been recorded on introduced trees such as weeping willow, black mulberry, pepperina, camphor laurel, London plane and Liquid amber. Photo Robert Ashdown.

The small and brightly-coloured Mistletoebird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum) is often blamed for spreading mistletoes. It is not the sole culprit however, as over 40 species of Australian birds (especially honeyeaters) are known to eat the mistletoe fruit. Other animals, including the dainty little Feathertail Glider are also very fond of mistletoe.

Mistletoe mate. The Mistletoe Bird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum), sometimes known as the Mistletoe Flowerpecker. Once I got to know the quiet call of these small but striking birds I was surprised to find them just about everywhere, from my street in the suburbs to the arid mulga-lands of western Queensland. Photo by Mike Peisley.

A Mistletoebird swallowing a mistletoe fruit. Boondall Wetlands, Brisbane. The lives of these birds are inextricably linked with mistletoe. This is the only Australian member of a widespread tropical family of flowerpeckers which feed almost exclusively on the fruits of mistletoes. The seed and its glucose-rich flesh are squeezed within the bill and swallowed. Within 25 to 60 minutes of being swallowed, the seeds are defecated, and are viscid, sticking to almost any surface. Almost all seeds germinate and if they have ended up on a compatible plant , a new mistletoe plant may establish itself. Photo Mike Peisley.

A female Mistletoebird with fruit. The digestive systems of the Mistletoebird are adapted to this specialised diet. Their stomach has become a simple sac able to digest little else other than a few insects and the alimentary canal facilitates the quick passage of seeds. Photo Mike Peisley.

Mistletoebird excreting seed. The germination inhibitor for mistletoe seeds is carbon dioxide within the fleshy fruit that surrounds the seed. Once this is removed the seed can germinate quickly. Photo Mike Peisley.

Germinating mistletoe seeds, Barakula State Forest. The fused cotyledons make an attachment by their tip, which eventually enters the host plant’s vascular system. Photo R. Ashdown.

Australian mistletoes have an ancient Gondwanaland lineage with closely related species found throughout the southern continents, as mistletoe expert Dr Gillian Scott points out in her excellent A Guide to the Mistletoes of Southeastern Australia. Dr Scott, quoting the Australian ornithologist Ken Simpson, also defends the Mistletoebird. According to Ken this bird is a relatively recent arrival in Australia, coming long after the split up of Gondwanaland and the evolution of our mistletoes. Australia has 90 species of mistletoes with about 35 of them found in south-east Queensland. Our mistletoes are contained in two families, the Loranthaceae (74 species) and the Viscaceae (14 species). The Loranthaceae has large colourful flowers and fruits whereas the Viscaceae has tiny flowers and small translucent fruits.

The Bulloak, or Slender-leafed, Mistletoe (Amyema linophyllum orientale) is one of the many types of mistletoe that are food plants for several species of Australian butterflies. This mistletoe is host to the Wood White (Delias aganippe), the Cooktown Azure (Ogyris aenone), the Amaryllis Azure (Ogyris amaryllis) and the Sydney Azure (Ogyris ianthus). Photo Craig Eddie.

There is still much to be found out about these fascinating plants and new species are still being discovered. As late as 2004 a new mistletoe was described from south-east Queensland. It was named Gillian’s Mistletoe (Muellerina flexialabastra) in honour of its discoverer Dr Gillian Scott. It is only known from the Darling Downs and Moreton Districts where it is found on the Hoop Pine (Araucaria cunninghami).

Mistletoes are not the demons that popular myth paints them. Rather, they are interesting and colourful members of Australia’s prolific floral wealth. So, please stop worrying about the roses and take time out ‘to smell the mistletoes’.

[This article was originally published in the Summer 2008 edition of the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service newsletter Bush Telegraph. Rod Hobson is a retired ranger (of 25 years’ service) with the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. A natural historian of long standing, in 2021 he was presented with Queensland Natural History Award by the Queensland Naturalists’ Club. ]

Extracts from the leaves of the Grey Mistletoe (Amyema quandang) have been shown to be active against laboratory strains of the Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus (golden staph) and Enterococcus faecalis. Both these bacteria can cause life-threatening infections in humans and are problems in hospital environments. It has been reported that Indigenous people of central Queensland would bruise the leaves of this species in water and drink the water for treatment of fever. Photo Craig Eddie.

Grey Mistletoe, Darling Downs, Queensland – providing essential nectar for birds, including visiting Painted Honeyeaters. Photos R. Ashdown.

Orange-flowered Mistletoe (Dendropthoe glabrescens). Mistletoe fruit is high in protein, carbohydrates and lipids. The leaves are high in nitrogen, phosphorous and trace elements. Mistletoes provide food for many native birds, mammals and insects especially during droughts and seasonal scarcity. Photo Craig Eddie.

Mistletoe in ancient River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), Barmah National Park, Victoria. Photo R. Ashdown.

Mistletoe leaves below River Red Gums (Eucalyptus camaldulensis), Barmah National Park, Victoria. Photo R. Ashdown.

Mistletoe in Rusty Apple (Angophora sp.), along the Maranoa River, Mount Moffatt section, Carnarvon National Park. Photo R. Ashdown.

Mistletoe fronting sandstone escarpment. Carnarvon Gorge, Carnarvon National Park. Photo R. Ashdown.

Brown Honeyeater feeding on nectar from a Grey Mistletoe (Amyema quandang). Jondaryan, Queensland. Photo R. Ashdown.

Are mistletoes ‘infesting’ woodlands?

Research does seem to indicate that mistletoe has become more abundant in woodland areas. Why is this so and is it really a problem?

Dr David Watson, a plant biologist from Charles Sturt University in Albury, New South Wales, has undertaken an ambitious 25-year project to learn more about the place of mistletoe in Australia’s environment.

“Studying 42 woodland remnants near Albury in New South Wales, Dr David Watson removed mistletoe from half of these areas, while the mistletoe of the other areas was left intact. David’s plan was to find out if the presence of mistletoe can influence how many other species live in an area, in particular, bird species. David believes that mistletoe is now ten times more abundant in south-east Australia than it was before white settlement. Mistletoes particularly target trees isolated in paddocks or by the sides of roads, making them all the more obvious to us.

However, David has argued that mistletoe ‘infestations’ are a symptom, not a cause of a much bigger problem. Changes in fire frequency and intensity, clearing trees and a reduction in native animals have all contributed. Mistletoe is killed by fire, and many areas are burnt far less often than before. Native animals such as possums, gliders and even koalas eat mistletoe, as do certain butterfly larvae. Once these species disappear from an area, there is nothing to keep the mistletoe in check. “But in the undisturbed bush, it’s an entirely different story,” David says, “The more mistletoes present, the greater the resources available for native animals, making the plants an important indicator of the area’s health.”

— from Misunderstood Mistletoe by Abbie Thomas, ABC Science online.

Preliminary results of his long term experiment suggest that more birds do, in fact, prefer to live where mistletoe is common. Woodland where mistletoe had been left intact had 17 per cent more total bird species, and of 44 woodland birds recorded, almost 70 per cent were more frequently seen in the intact sites than the sites without mistletoe. David says many birds prefer to nest in mistletoe because it provides shade and cover. Mistletoe nesters include the Grey Goshawk, several species of pigeon and dove, honeyeaters, wattlebirds, friarbirds and many others. Quite a number of butterfly larvae also feed on mistletoe, and some caterpillars can completely strip a mistletoe of its leaves in a matter of months, providing another natural check on mistletoe.

The larvae of the Common Jezebel Butterfly feed exclusively on Mistletoe leaves. In his book on southern Australian mistletoe species, David Watson lists 23 butterfly species whose larvae depend on mistletoe as a principal food source, plus an extra four species that include mistletoe among the plants they eat. A number of species of moth also have larvae that eat mistletoe. Photo R. Ashdown.

According to naturalist and photographer David Muirhead, various Australian native Santalum species of plants (including bitter and sweet quandongs, desert plum and sandalwood) have often been likened to mistletoes, in that they ‘parasitise’ the roots of nearby flowering plants — from grasses to shrubs and trees. The larvae of certain butterfly species are known to feed on both mistletoes and Santalacea trees and shrubs. One strikingly attractive example in David’s home state of South Australia is the Wood White butterfly, pupae of which are seen here anchored to the sturdier branchlets of Santalum acuminatum growing in the Northern Normanville dunes. Photo courtesy David Muirhead.

Scarlet Honeyeater feeding on Mistletoe flower nectar, Boondall Wetlands, Brisbane. Photo by Mike Peisley.

Brown Honeyeater in search of Mistletoe nectar. The brightly-coloured tubular corollas attract the bird, while the long stamens are ready to dab pollen on the bird’s forehead. Photo Mike Peisley.

As the biology of mistletoe becomes better understood, biologists are urging that they be managed with an eye on the underlying causes of the problem. One place that did this recently was in the Clare Valley in South Australia where local residents were concerned about mistletoe infestations in local blue gums. They made it their business to learn more about the biology of mistletoes. Although some of the bigger infestations were manually removed, natural animal predators were also encouraged back to the area by fencing off areas and planting trees.

Pale-leaf Mistletoe (Amyema maidenii), growing in Mulga (Acacia stowardii), Hood Range, far western Queensland. Photo R. Ashdown.

The same species, closer view. The varied and subtle forms and colours of Australian mistletoe make them fascinating photographic subjects. Photo R. Ashdown.

David says the best way to control mistletoe infestation is by addressing the underlying cause: such as putting up nesting boxes to encourage possums and gliders, control burning of the understorey to kill excess mistletoe, and encouraging regeneration of native plants. But he takes his argument further. Mistletoe, he says, could be a powerful tool in the management of forest plantations of species such as blue gum. At the moment, such plantations are plagued by chewing insects such as beetles, and require huge expenditure on pest control. But if every, say, 100th tree were to be seeded with a mistletoe, these would eventually grow, flower and attract insect-eating birds and possums which would also eat the problem insects, effectively turning a plant pest into a natural pest controller.

Lysiana subfalcata can grow on a number of hosts, including other mistletoe species. Bunjinie, Jimbour. Photo R. Ashdown.

Native mistletoe stands out when deciduous garden trees in Toowoomba lose their leaves. Photo R. Ashdown.

The Painted Honeyeater and a mistletoe migration

As mentioned above, mistletoe plays a significant role in the lives of many Australian birds, providing both food and habitat. Apart from the Mistletoebird (Dicaeum hirundinaceum), at least 40 species of Australian birds, including honeyeaters, are known to eat mistletoe fruit. Additionally, mistletoe provides nesting and roosting sites for various birds, offering protection from weather and predators.

Painted Honeyeater (Grantiella picta), Jondaryon, Queensland. The survival of these beautiful honeyeaters depends on mistletoe. Photo R. Ashdown.

The Painted Honeyeater (Grantiella picta) is the most specialised of Australia’s honeyeaters, relying heavily on mistletoe.

Classified as ‘Vulnerable’ at a national level, this bird lives in parts of south-eastern Australia, southern Queensland, and some parts of the Northern Territory. Most honeyeaters have a mixed diet, consuming nectar, fruits and insects from a range of sources and locations. The Painted Honeyeater however, is a frugivore, a dietary specialist dependent on the presence of mistletoe plants and their fruit. Painted Honeyeater abundance is usually linked to the availability of misteltoe fruit and nectar.

Painted Honeyeaters often eat mistletoe fruits during their breeding season, and feed on mistletoe nectar when fruit is scarce. They build cup-shaped nests from rootlets, plant fibres and spiderwebs, and hang them from trees that have mistletoe. The birds seem to select nest sites in habitats where mistletoe is prevalent.

Painted Honeyeater in mistletoe, Jondaryan, Queensland. Mistletoe fruit was consumed as a food source by many Aboriginal nations. The spreading of mistletoe by the painted honeyeater may have contributed to the availability of mistletoe fruit for indigenous peoples throughout the painted honeyeater’s distribution. Photo R. Ashdown.

Fruit of the Grey Mistletoe (Amyema quandang) is a source of carbohydrates, protein and water, and accounts for a significant amount of the diet of Painted Honeyeaters. Myall Creek Nature Reserve, Jondaryan, Queensland. Photo R. Ashdown.

Painted Honeyeaters exhibit a seasonal north-south movement, governed mainly by the fruiting of mistletoe, with which its breeding season is closely matched. After breeding, many birds move to semi-arid regions such as north-eastern South Australia, central and western Queensland, and central Northern Territory.

Ensuring the protection of habitat, including the woodlands required by this species, amd the mistletoe within them, is a key factor outlined within the national recovery plan for the long-term conservation of this vulnerbale species.

Strategies From the National Recovery Plan for the Painted Honeyeater (Grantiella picta) reflect the significance of mistletoe and its place within broader ecosystems:

- Conduct strategic planting of host trees and re-establishment of mistletoe. Host trees include planting of acacia species (particularly A. pendula or A. homalophylla) to restore Brigalow, Boree and Yarran woodlands and connect fragmented patches, particularly in areas where Painted Honeyeaters are known to occur and breed. Biodiversity funding and investment programs have included Brigalow, Boree and Yarran woodlands as priority areas for restoration.

- Target areas of box-gum woodlands and box-ironbark forests for restoration and re-seeding ofmistletoe particularly on the inland slopes of the Great Dividing Range in New South Wales, Victoria and southern Queensland.

At least five species of the mistletoe genus Amyema have been documented as being a food source for the Painted Honeyeater, which in turn assists in dispersal of the mistletoe by excreting the seed. Photo R. Ashdown.

‘Entangled partnerships’ — mistletoe and mutualism

For a final perspective on mistletoe, I have reproduced the text from a 2014 blog post by Deborah Bird Rose.

Deborah Bird Rose (1946-2018) was an Australian-based anthropologist and ethnographer, who took an ecological, multi-species/multi-disciplinary approach to her research. She wrote about the ‘entangled quality of llfe’, where everything living depends on and supports connectivity. Her research explored the idea, and moral ramifications of, humans as part of a world of connection to other species, and to our own species. Her work was grounded in a “profound sense of the connectivities and relationships that hold us together.”

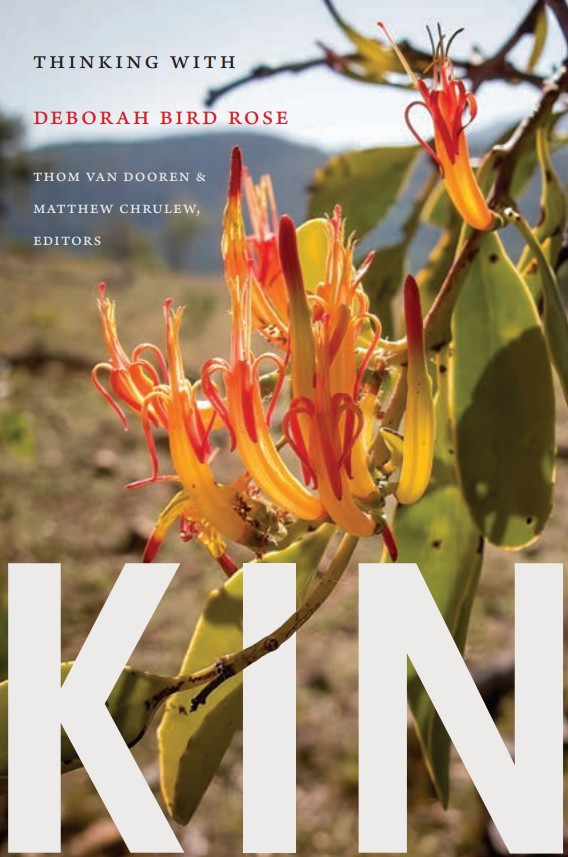

I discovered Deborah Bird Rose when I was contacted about the use of an image of mine of mistletoe (that had been spotted an earlier version of this blog post) for the cover of a book of essays honouring her work: Kin: Thinking with Deborah Bird Rose. I enjoyed reading Deborah’s work (including that which covered flying foxes, one of my favourite creatures) and even finding some online recordings of her lectures. It was honour to have an image of mine of the cover of this thought-provoking book.  While Deborah Bird Rose’s blog Love at the Edge of Extinction is no longer online, I was able to finally track down an archived 2014 post of hers (thanks Vicky). In presenting the text of Deborah’s engaging online essay here, I am aware that I do not have copyright clearance. Please contact me if you have concerns about me reproducing this text.

While Deborah Bird Rose’s blog Love at the Edge of Extinction is no longer online, I was able to finally track down an archived 2014 post of hers (thanks Vicky). In presenting the text of Deborah’s engaging online essay here, I am aware that I do not have copyright clearance. Please contact me if you have concerns about me reproducing this text.

Under the Mistletoe

Deborah Bird Rose

Keystone species ‘punch above their weight’, to use a popular metaphor. They contribute more to their ecosystems than their numbers would indicate. Charismatic top predators such as wolves and dingoes are great examples of keystone species. They generate the trophic cascades that enhance whole systems of life including the geophysical foundations (discussed here). But as the fascinating ecologist Stephan Harding tells us:

‘You never know who the big players are in the wild world.’

To my mind one of the least likely ‘big players’ is mistletoe. Can a parasite actually be a keystone? Surprisingly, the answer is ‘yes’. Not only is mistletoe good for kissing, this great cohort is a ‘keystone resource’.

Let us enter the entrancing world of mistletoe through symbiotic mutualism. A relatively non-technical definition is ‘two or more species that live together to their mutual benefit’. Although the idea of symbiosis was not the dominant paradigm for much of the 20th century, a growing body of research is showing that it complements competition and is utterly fundamental to life on earth and is part of how every creature lives. The great biologist Lynn Margulis declares:

‘We are symbionts on a symbiotic planet.’

Mistletoe, it turns out, is a highly eclectic and inclusive symbiotic mutualist. One of the main families all around the world, and a prominent player in Australia, is Loranthaceae – a family of mistletoe with about 1,000 member species. Most of them are ‘obligate, stem hemiparasites’. This means that they can only live by being attached to another plant (obligate), that they attach to stems (not roots), and that while they get water and some nutrients from their host, they are also able to photosynthesise.

Yellow-flowered Mistletoe (Dendropthoe vitellina), Sundown National Park. Moss and Kendall list 13 species of butterfly that are associated with this mistletoe! Photo R. Ashdown.

The story of mistletoe mutualisms is all about entanglements of interdependencies, nutrient cycles, and seductions. Loranthaceae are themselves deeply dependent. First there is dependence on the tree or shrub on which they grow. No host, no parasite. Next, there is dependence on birds and bees to pollinate. No pollination, no seeds, no future generations. Then there is dependence on birds, in particular, to eat the fruits and disperse the seeds. No dispersal, very little chance of germination and growth. And there is dependence on the leaf-eaters: no browsing means too much mistletoe growth leading to multiple deaths and disasters.

If mistletoes are to survive they have to entice and nourish their mutualists. The brightly coloured flowers are powerful attractors of pollinators, and the nectar is not only high in sugars, but also fats. Some of the Australian Loranthaceae produce nectar containing droplets of pure fat. The berries are highly visible, abundant and full of nutrition. Worldwide, many ‘folivores’ eat the nutritious leaves: deer, camels, rhinoceroses, gorillas and possums, amongst many others. Their adaptive edge goes beyond mere provisioning and involves dazzling abundance. The most awesome interdependence is between mistletoes and their mutualist mistletoe birds. ABC Science journalist Abbie Thomas wrote a delightful account:

‘Many mistletoes continue to flower in drought or during winter, when few other blossoms are available. Indeed, they are often the only local source of nectar and pollen during hard times. Packed with sugar and carbs, mistletoe fruits are good tucker, not just for the ubiquitous mistletoe bird, but also for cuckoo-shrikes, ravens, cockatoos, shrike-thrushes, woodswallows, bowerbirds, and even emus and cassowaries. The mistletoe bird plays an important role in the mistletoe plant’s life cycle. The life of most mistletoes begins when a viscous, gluey seed drops onto a branch from the rear end of the brilliantly coloured black, red and white Mistletoebird. Found throughout Australia, these birds are highly mobile and go wherever mistletoe is in fruit. Once eaten, the seed of the fruit quickly passes through the bird, emerging just 10-15 minutes later. The sticky seed fastens onto the branch, although many seeds fail to adhere, and are lost.

Within days, a tiny tendril emerges from the seed, growing quickly and secreting a cocktail of enzymes directly onto the corky outer protection of the branch. Unable to resist the onslaught, the bark yields a small ulcer-like hole into which the tendril probes, seeking its way down into the sappy tree tissue until it hits paydirt: the water and mineral-rich plumbing of the tree.’

Mutualisms are entanglements of interdependencies. The host tree supports its mistletoes physically and nutritionally, and it also buffers them against the vicissitudes of climate uncertainty. So, too, mistletoes support other species and provide a buffer against fluctuations and uncertainties. A study from Australia shows that mistletoes have extended nectar and seed producing periods, and that within a given region nectar and fruit are available from one or another mistletoe species all year round. In addition, as mistletoes are host to so many insect species, the insect-eating birds also get the benefit. Mammals join the feast, eating leaves, seeds and flowers. Possums are amongst the main leaf eaters, and are seasonally dependent on mistletoe.

Along with all the creatures who consume mistletoes, there is yet another entourage that benefits. Some animals build their nests in the mistletoe where they get some protection from the elements and predators. The action of the mistletoe itself increases hollows in trees, and so all the creatures that nest in hollows get the benefit. A further benefit is that their presence in trees alters the forest canopy and reduces the severity of bushfires.

In life systems, what goes around comes around. The host tree or shrub gets a steady rain of litter, droppings, and other organic matter that become part of the nutrient cycle, benefiting both the host and other plants in the area. In short, the benefits of mistletoes pass through the lives and bodies of many species before turning into nutrients to be drawn up by hosts and tapped into by mistletoes.

The relationships work because of the extravagant generosity of interdependence: highly nutritious nectar produced by bright showy flowers; shiny seeds loaded with carbs and sugars; mistletoe birds with their gorgeous red feathers, lovely song, and fertile poop; gliders and possums; butterflies who visit, eat, and reproduce.

There is an association between songbirds and mistletoe, and as new evidence is showing that both groups have their origins in ancient Gondwanaland, perhaps there is more to this old and beautiful alliance than is yet properly understood. I found myself totally captivated by a story shared by Andrew Skeoch, a sound recordist specialising in the sounds of nature. He recorded a mistletoe bird in full song, and inadvertently also recorded the fact that this talented little creature was singing and pooping at the same time. Something about this bright little bird creating and performing musically, while depositing mistletoe seeds securely wrapped in glue and fertiliser seems almost magical in its joyfulness.

Mistletoe on Mulga (Acacia aneura), Myninya Lookout, Currawinya National Park – lands of the Budjiti People. Dr Russell Barrett, a botanist from the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney says mistletoes were primarily a source of food for Indigenous communities because their sticky fruits were sweet. “The medical properties of particular species were even used to treat common colds. They were also an important biological health indicator. The presence of mistletoe was also an important indicator for the condition of country, as all species are sensitive to fire, so too much burning and they disappear from the landscape.” – AG, 2018. In his column for AG, science writer Tim Low noted that the Christmas tree (a mistletoe) was significant to the Noongar people of Western Australia as they believed it was the resting place of the dead. Photo by R. Ashdown.

It is good to recall that there is an old European history of respect. Mistletoe is sacred to Druids (contemporary and ancient), and it is still a customary Christmas decoration. Hung over the threshold, it invites people to kiss. In earlier days it was said to be able to find buried treasure, keep witches away and prevent trolls from souring milk! It would be good also to recall that Aboriginal Australians respect mistletoe as a food for humans and for many other creatures. In North Australia, where so much of my learning has taken place, people give berries to children, but adults avoid them. Perhaps they are aware that growing children have a particular need for the high nutritional value of mistletoe.

At this time, many people think mistletoe is a pest. The term ‘parasite’ conjures negative imagery, but the larger issue, at least in Australia, is that in some areas mistletoes are over-abundant. Trees are dying, and something has gone askew because mistletoe cannot thrive if the host dies. The renowned science writer Tim Low tells us that the loss of possums, those folivores who love their mistletoe, is a key. “Foxes, by preying on mistletoe-munching possums,” set up conditions where mistletoes can grow out of control. Possums are only prey to foxes when they come down out of the trees. Along roadsides and on farms, they are at risk. Within forests where they can remain up in the trees possums thrive and mistletoe is contained.

So, what would partnership rewilding be like if the focus were on mistletoes and their ‘ground up’ trophic dynamics? First, it would involve fewer foxes and more possums. Here the answer is readily to hand in the form of the dingo. As I have been reporting in other essays, the evidence is overwhelmingly clear that dingoes reduce the numbers of invasive species such as foxes and cats, and promote the viability of smaller native marsupials such as possums.

Second, it would involve on-going health and reproductive capacity of more extensive stands of trees. Here the answer is readily to hand in the form of flying-foxes. Their pollination is utterly crucial to the future of forests and woodlands in Australia, and their lives and livelihoods are central to partnership rewilding.

Third, it would involve changes in human thought and action. Not everyone thinks mistletoes are innate pests, but, as the great mistletoe scientist David Watson indicates, “pretty much all of the public’s perceptions about Mistletoe are fundamentally incorrect.” I want to be clear that Aboriginal people are not likely to hold these misperceptions. Here, as with other matters, the limitations of the mainstream public cannot readily be attributed to everyone. Having said that, I want to set up camp, metaphorically at least, under the mistletoe. Here the kiss of life is sensuous, continuous, and diverse.

I hope others will join me, and I rather hope we won’t get pooped on! Let us open our lives to the great, complex, on-going, joyful, benefit-rich, exuberant and dazzling generosity that holds entangled interdependencies together. A camp in the midst of all these mutualisms is place of coming-forth for those whose flows of life and death are achieved together. These entangled partnerships have co-evolved over millions of years, and if the human newcomer can partner in with them, we may yet become part of ecosystems that will hold together in this time of flux and uncertainty.

This was the third in an online series of essays by Deborah Bird Rose on partnership rewilding. The others include: Partnership Rewilding with Flying-Foxes, and Partnership Rewilding with Predators. [Retrieved from Trove.]

References

- David M Watson (1969), Effects of Mistletoe on Diversity, Emu.

- HA Ford and DC Paton, Eds, (1986), The Dynamic Partnership: Birds and Plants in South Australia, The Flora and Fauna of South Australia Handbooks Committee.

- Dr Gillian Scott (1999), A Guide to the Mistletoes of South Eastern Australia. Toowoomba Field Naturalist Club.

- David M Watson (2001), Mistletoe – a Keystone Resource in Forests and Woodlands Worldwide, Annu.Rev.Ecol.Syst vol:32 pp:210-49.

- David M Watson (2001), Nature’s One Stop Shop, Wingspan magazine.

- Abbie Thomas (2001), Misunderstood Mistletoe. ABC Science online.

- David N Norton (2002), Lessons for ecosystem management from management of threatened and pest loranthaceous mistletoes in New Zealand and Australia, Conservation Biology vol:11 pp:759-769.

- Watson David M. and Herring Matthew (2012), Mistletoe as a keystone resource: an experimental test, Proc. R. Soc. B.2793853–3860.

- Deborah Bird Rose (2014), Love at the Edge of Extinction (blog site).

- David Watson (2015), Mistletoe: The Kiss of Life for Healthy Forests. The Conversation.

- John T. Moss and Ross Kendall (2016), The Mistletoes of Subtropical Queensland.

- Angela Heathcote (2018). Australia is the real home of mistletoe. Australian Geographic.

- David M. Watson (2019), Mistletoes of Southern Australia.

- Jane Canaway (2019), Unveiling the misunderstood magical mistletoes of Australia ABC Everyday webpage.

- Deborah Metters and John Moss (2019), Mistletoes: their biology and ecology. Land for Wildlife SEQ newsletter.

- Australian Government (2021), National Recovery Plan for the Painted Honeyeater (Grantiella picta).

Information and resources

- Mistletoes in Australia — Australian National Herbarium. This is a fabulous on-line resource on Australian mistletoes.

- Ecology of parasitic plants – Dr David Watson’s blog.

- The Botanical Art of Gillian Scott. See article on page 6 of the Journal of the friends of the National Botanic Gardens, Dec 2018. Gillian Scott was the first Australian botanical artist to win the coveted Gold Medal of the Royal Horticultural Society (U.K.) in open international competition with her display of 22 species of Australian mistletoes.

- Mistletoebird. Birdlife Australia.

- References for further information on Australian Mistletoes. For anyone interested in Australian mistletoe cultivation.

With thanks to Rod Hobson, Martin Ambrose, Victoria Cooper, David Muirhead, Richard Jeremy, Annette Dexter, Deborah Bird Rose, Mike Peisley and Bernice Sigley.

Great stuff, Mistletoes are one of my favorites, love that article Misunderstood Mistletoes.

Remarkable information and superb pictures, Rob. I never realized just how beautiful and important they are.

Thanks Russ and Martin. Cheers, Rob.

I didn’t know Mistletoe was native to Australia. While all we see are dried, flattened, small lobes during the holidays, I think I’d prefer smooching under a tree with live mistletoe growing on it.

Hope you are well Charly! Cheers, Rob.

Fantastic blog & photography!! Thank you 🙂

Thanks mate, glad you liked the mistletoe story. Cheers and all the best, Rob.

Brilliant and fascinating presentation

Thanks, David, much appreciated.

Came to your site to get the real lowdown on mistletoe in Australia, I am also South Australian , was concerned only because I used to see a mistletoe eradication zone on my way to Yorkes, thought they were a threat to host trees, thanks for putting me right, part of the healthy arbor of Oz, got it

Thanks for the message, Andrew! All the best, Rob.

The photo in Barakula State Forest isn’t Amylotheca dictyophleba; it’s one of the Lysiana species, possibly Lysiana exocarpi.

Thanks, Annette – corrected.